Drivers of House Price Growth in New Zealand

Executive summary

This report aims to deliver the following insights and analyses:

an independent review of the factors of house price growth (HPG) in New Zealand

a range of descriptive statistics of the HPG and its drivers over the last fifty years.

Our review includes both the academic and grey literature. We provide a list of suggested future studies to improve our understanding of the factors of HPG in New Zealand.

Despite being one of the national priorities, New Zealand’s HPG has not been discussed and analysed thoroughly and the available literature does not provide a comprehensive understanding of the drivers of HPG

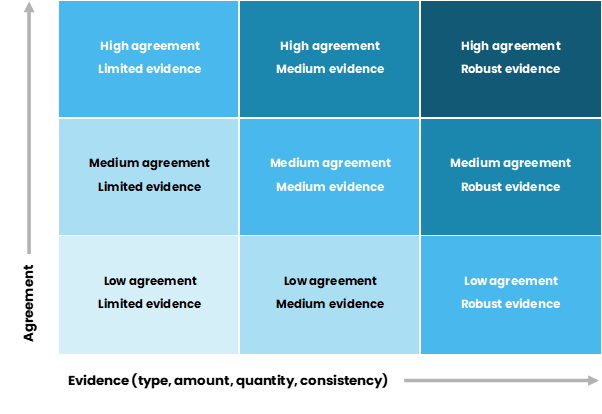

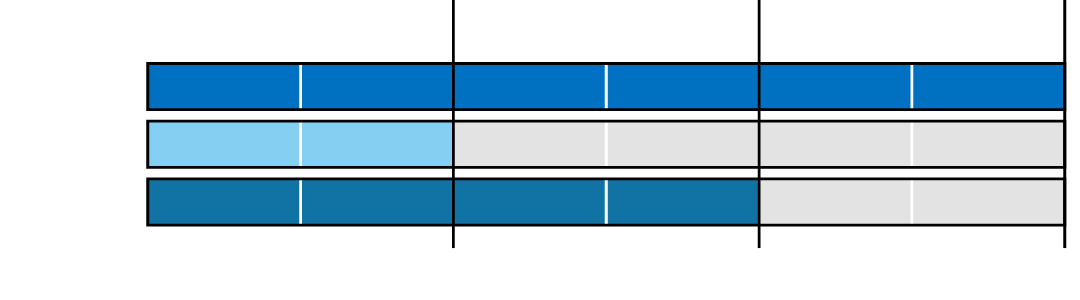

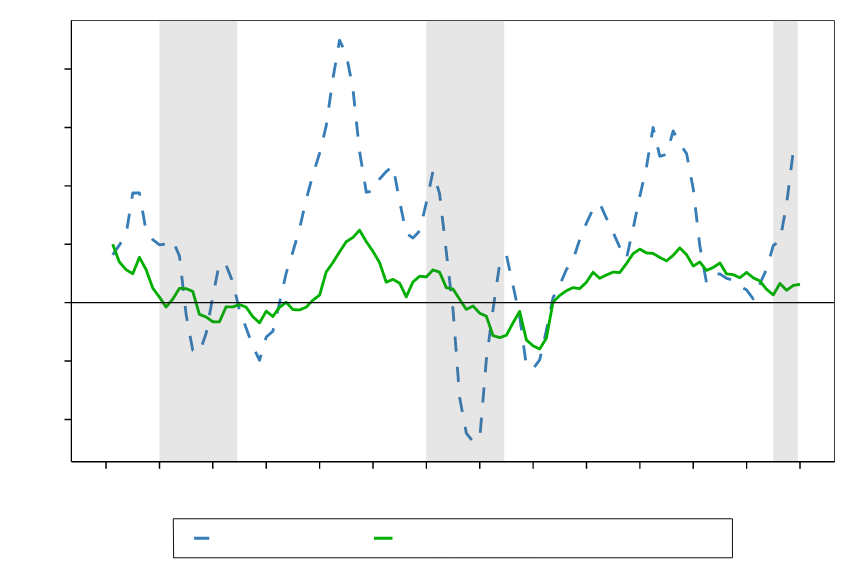

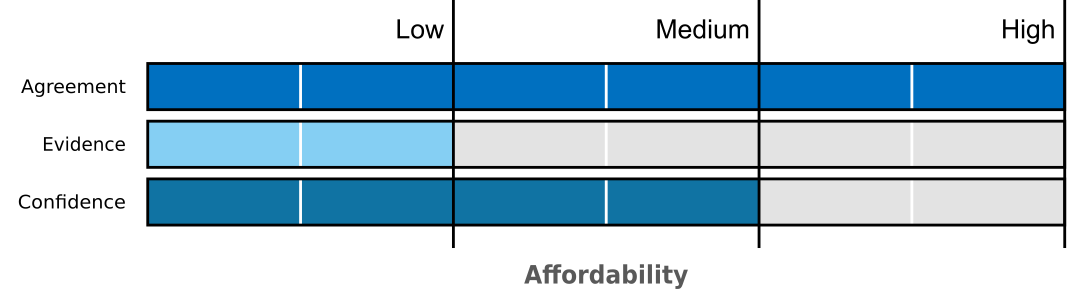

With an annual growth of 3.1 percent over inflation, the HPG has led to significantly lower housing affordability with a widening gap between low- and high-income groups. This has led to high economic costs to the New Zealand economy, with a minimum $1.1 billion annual cost through lower labour productivity levels.1 The available literature provides information about the impact of supply and demand factors on house prices. This provides us with an understanding of the relative cost of the factors of supply and demand capitalised into the house prices. However, the impact of the factors on house price growth, and the relative contribution of each of these factors on HPG is not clear. Most of the available literature provides an understanding of the impact of each factor affecting house prices in isolation. While there has been extensive analysis of some factors, such as the impact of regulation on housing supply, other drivers of HPG have been neglected. Table 1 shows our evaluation of the level of agreement, the strength of evidence and the overall confidence with the impact of each factor of supply and demand on HPG. We discuss this further in the following paragraphs.

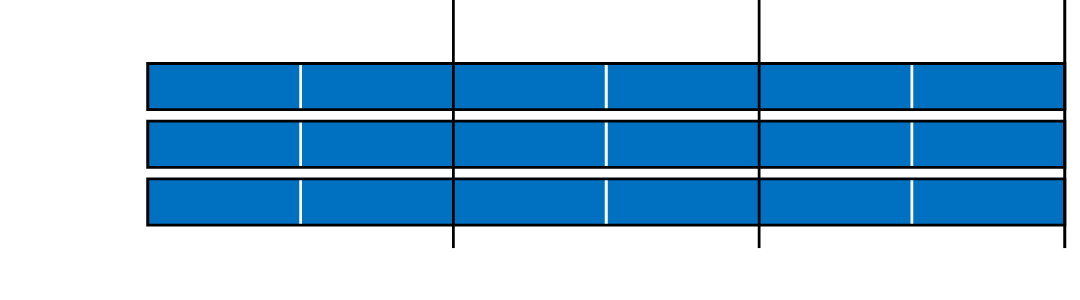

Table 1 Evaluation of agreement, strength of evidence and overall confidence

| Impacts of the factors of supply | Agreement | Evidence | Confidence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Impact of regulations | High | High | High |

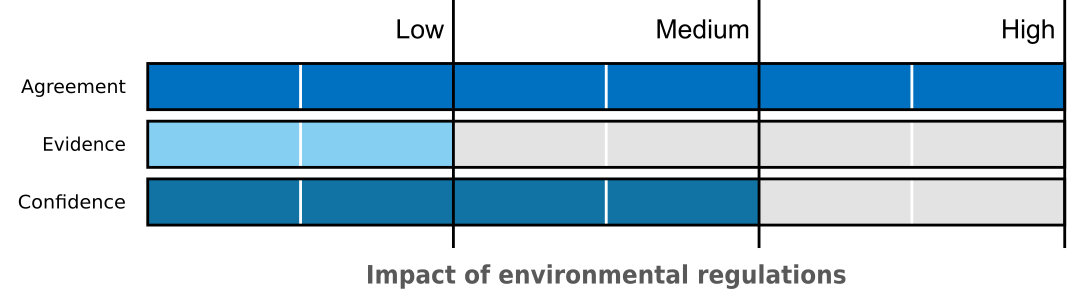

| Impact of environmental regulations | High | Low | Medium |

| Availability of infrastructure | High | Low | Medium |

| Supply chains and construction cost | High | Low | Medium |

| Impacts of the factors of demand | Agreement | Evidence | Confidence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Affordability | High | Low | Medium |

| Availability of finance | Low | Low | Low |

| Household size | High | Low | Medium |

| Monetary policy and mortgage rates | High | High | High |

| Population and migration | High | Medium | Medium |

| Tax policy and housing subsidies | High | Low | Medium |

Source: Principal Economics.

Despite the extensive focus of the literature on the costs imposed by some factors, the studies do not provide enough information to inform policy development. For example, the extensive literature on the costs imposed from regulation, does not provide robust evidence of the role of the Resource Management Act (RMA) versus the role of other planning regulation. The RMA provides a framework for sustainable management of natural and physical resources. While the RMA does not explicitly require any supply side regulation, it provides a regulatory framework for the implementation of the planning regulations. The planning regulations cite the RMA as the driver of the zoning regulations. The linkages between the RMA and zoning regulations are untested.

Using overly simplified indicators for the factors of HPG leads to unintended policy outcomes

Some indicators of affordability, such as price to income and price to rent ratios, are overly simplified and their implications for the analysis of affordability (and HPG) in New Zealand is not clear. There are advantages in using simplified indicators of HPG and its determinant factors – particularly, for ease of understanding and high-level policy discussions. However, we observe a trend in using overly simplified indicators for policy advice, without accounting for the underlying complexities. This can lead to unintended policy outcomes.

On the supply side…

Our review suggests that the regulatory barriers, such as building height limits and the viewshaft policies, are costly and are a driver of HPG. However, there is no robust evidence that, in the absence of regulations, the available resources (labour, capital and technology) have the capacity required for increasing housing supply.

Planning regulations have led to inefficiencies in the land market and higher house prices

There is extensive literature on the costs imposed from planning regulations, such as building height limits and urban growth boundaries. There is a high level of agreement that regulation is associated with high cost to the housing market (and the economy). Most of the studies provide high quality evidence supporting this hypothesis.

Our review suggests that the RMA and environmental regulations are associated with more stringent land use regulations, leading to HPG

While the studies estimating the impacts of regulation agree on the costs associated with planning regulations, the evidence on the impact of environmental regulation and RMA restrictions is limited. Our review suggests that the environmental regulations (and the RMA) add to the costs of housing. Recent literature suggests that a reform of the Resource Management system can lead to lower economic and social costs through providing higher certainty around zoning regulations, and a more permissive regulatory regime that allow more flexibility in housing supply.

However, from the available literature, we do not know the extent to which current house prices are driven by environmental regulation, inefficiencies raised from uncertainties associated with inconsistent and opaque Acts and reforms, lack of national or local direction, or poor monitoring of the system

The RMA provides guidelines for planning regulations (and zoning). Given the overlaps, it is not clear if the impacts are driven by the RMA or councils’ desire for using zoning tools to intensify.

The inefficiencies in the infrastructure planning system are drivers of high house prices, but the literature does not provide robust evidence

The literature agrees that the lack of infrastructure is a driver of planning regulations and therefore is a reason for lower responsiveness of housing supply to increases in house prices. The current literature includes discussions of:

the lack of infrastructure being the reason for costly planning regulations; and

the potential misalignment between the plans and zoning regulations

The available literature does not provide robust evidence for the impact of infrastructure on HPG.

Inefficient supply chains and increased construction costs have contributed to HPG

The larger size of houses and increased construction costs, due to the introduction of new materials and the requirements of the Building Act, has been cited as a driver of HPG. The lack of suitable technology, such as modular housing, and the small scale of the construction sector are additional factors that are cited. However, the evidence is limited. It is particularly not clear how the cost of construction will change in the absence of other (regulatory) constraints.

On the demand side …

Our review suggests that the factors of demand, such as lower interest rates and increased immigration, have been some of the reasons for the significant HPG over the last twenty years. The number of studies that have isolated the factors of housing demand in New Zealand is smaller than the number of studies of the factors of supply. This is partly because the factors of housing demand have wider economic impacts beyond the housing market and therefore it is difficult to identity policy instruments that only affect house prices. For example, a change in interest rate affects all other economic activities, as well as the housing market.

Increases in households’ mortgage serviceability, driven by lower mortgage rates, have contributed to HPG

Based on the literature, a lower interest rate increases a household’s ability to pay for a house. If housing supply is responsive to the higher ability of a household to pay, then the increase in supply avoids significant increases in house prices. But since housing supply has not been responsive to households’ higher mortgage serviceability levels over the last decade, the lower interest rates have led to higher house prices. The impact of monetary policy highly depends on the other (supply) factors. While the long-term impact of monetary policy depends on the speed at which supply can respond to demand side factors, in the short- term monetary policy will likely always have a direct impact on house prices because supply lags behind demand, and it takes time to build more homes. The evidence-based literature on the impact of macroprudential policies2, including Loan to Value Ratio (LVR), is limited.

Population growth increases demand for housing and leads to HPG, when housing supply is inelastic

The pull and push factors of migration include the attractiveness of the job market, the availability of amenities and facilities and the cost of living – which is highly interrelated with housing costs. This cycle in factors of migration and house price growth leads to complexities in identifying a causal inference about the impact of population growth on house price. This has been reflected in our summary of the estimated impact of increases in population on house prices (ranging between 0.02 and 12 percent).

Decreasing household size and changes in features of households may contribute to HPG in the future

There has been a significant decrease in the size of households over the last decades from an average of 3 persons per household (PPH) in 1981 to 2.7 in 2001 and 2.6 PPH in 2013. A growing number of households increases the demand for dwellings and leads to higher house prices. For a population of 5 million, a change from 3 PPH to 2.6 PPH is associated with a need for more than 250,000 additional dwellings. Projections suggest that the number of households will increase further because of the projected decrease in household size to 2.5 PPH by 2038.

The available literature does not provide enough evidence-based analysis of the likely impact of tax and subsidy policies

Taxes are considered as a solution to decrease speculative behaviour and to raise funds for infrastructure investments. There is a range of tax policies, including development contributions, financial contributions, and betterment taxes. Both taxes and subsidies (depending on their type) are associated with distributional effects across different income groups, types of buyers, and regions.

It is critical to develop a comprehensive robust housing model for New Zealand

The current models used by the Reserve Bank, the Treasury and the Ministry of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) do not provide any extensive tool for forecasting house prices in New Zealand. Our assessment of the available information suggests that the models are not suitable for the assessment of housing policies. We are not confident that the available models provide a robust framework for the assessment of macroprudential policies. For a policy targeting the wellbeing of New Zealand population, it is critical to assess the distributional impacts of policies, which the current models do not provide.

Table of Contents

1.1. Methodology of literature review

1.2. Description of HPG and its factors

1.3. HPG and housing affordability

2. Impact of the factors of supply

2.2. Impact of the RMA and environmental regulations

2.3. Availability of infrastructure

2.4. Supply chains and construction costs

3. Impact of the factors of demand

3.2. Monetary policy and mortgage rates

3.6. Tax policy, housing subsidies and other interventions

4. Discussion and future research

Figures

Figure 1 IPCC’s uncertainty framework

Figure 2 Example of the uncertainty assessment diagram

Figure 3 Nominal changes in housing prices

Figure 4 House price growth and residential floating mortgage interest rates

Figure 5 International changes in real house price

Figure 6 Real housing cost indices

Figure 7 Residential rental prices

Figure 8 Growth in employment density and real house prices

Figure 9 Building consents and population growth

Figure 10 Distribution of new dwellings in Auckland 2006 - 2018

Figure 11 Timeline of investment in capital stock

Figure 12 Timeline of housing related development

Figure 13 House price to household income median multiple

Figure 14 Housing affordability/mortgage serviceability over time

Figure 15 Housing affordability/mortgage serviceability at different income levels

Figure 16 Homeownership rate in New Zealand

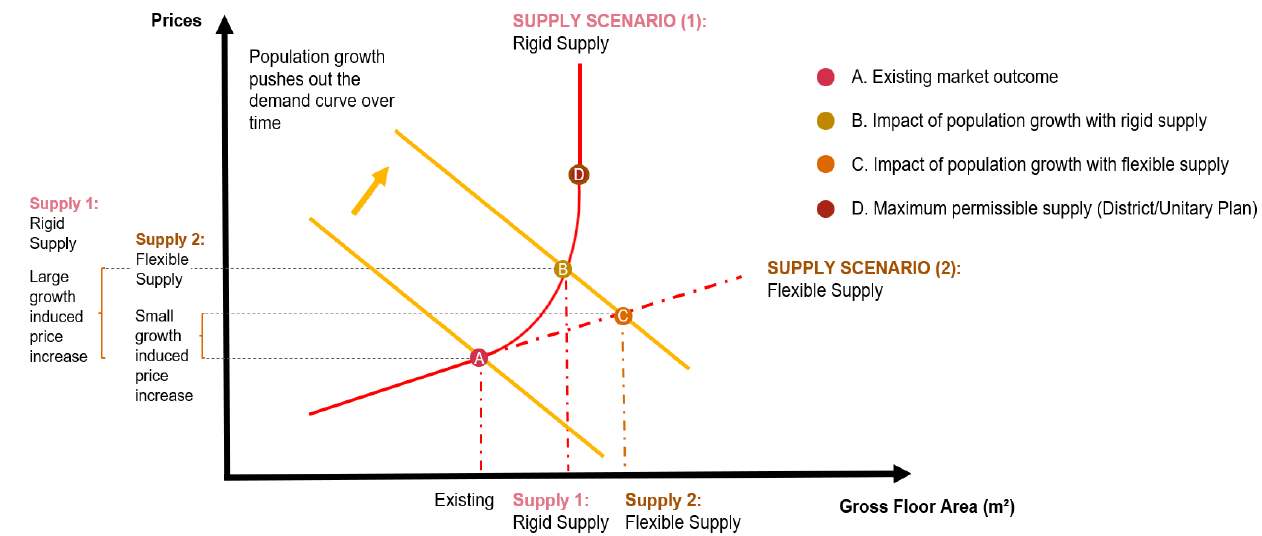

Figure 17 Impact of rigid supply on house prices

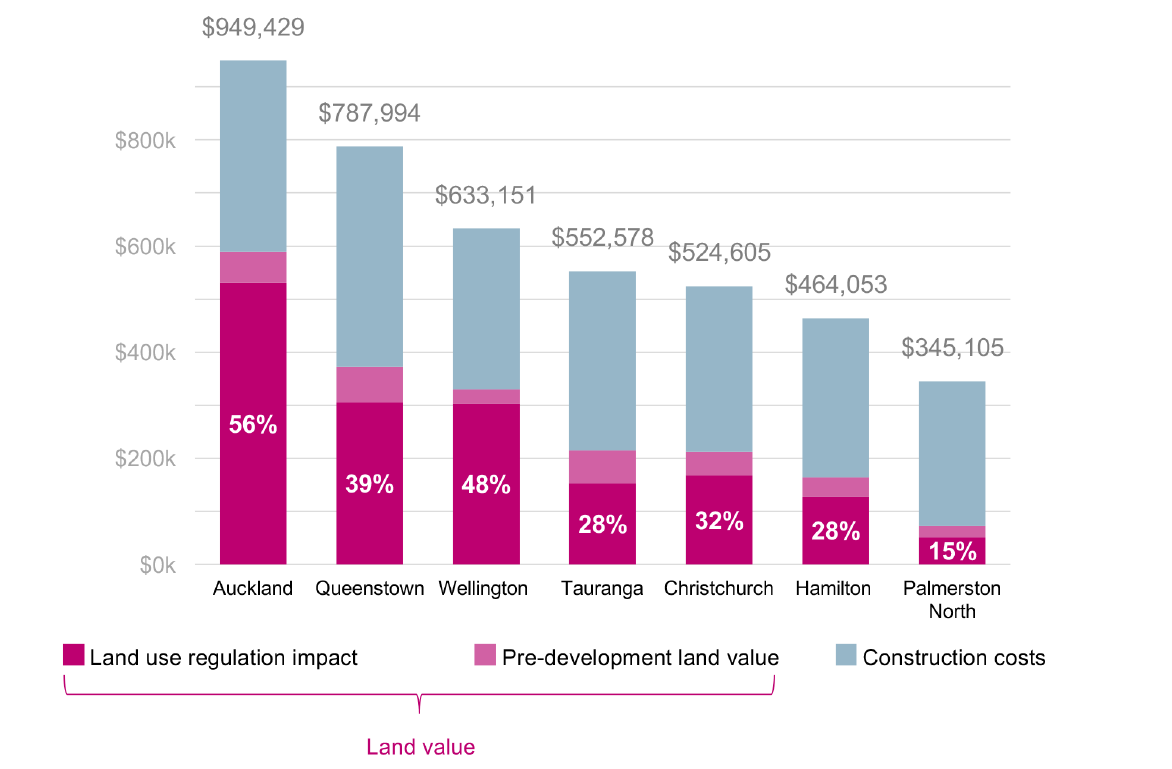

Figure 18 Land regulation costs

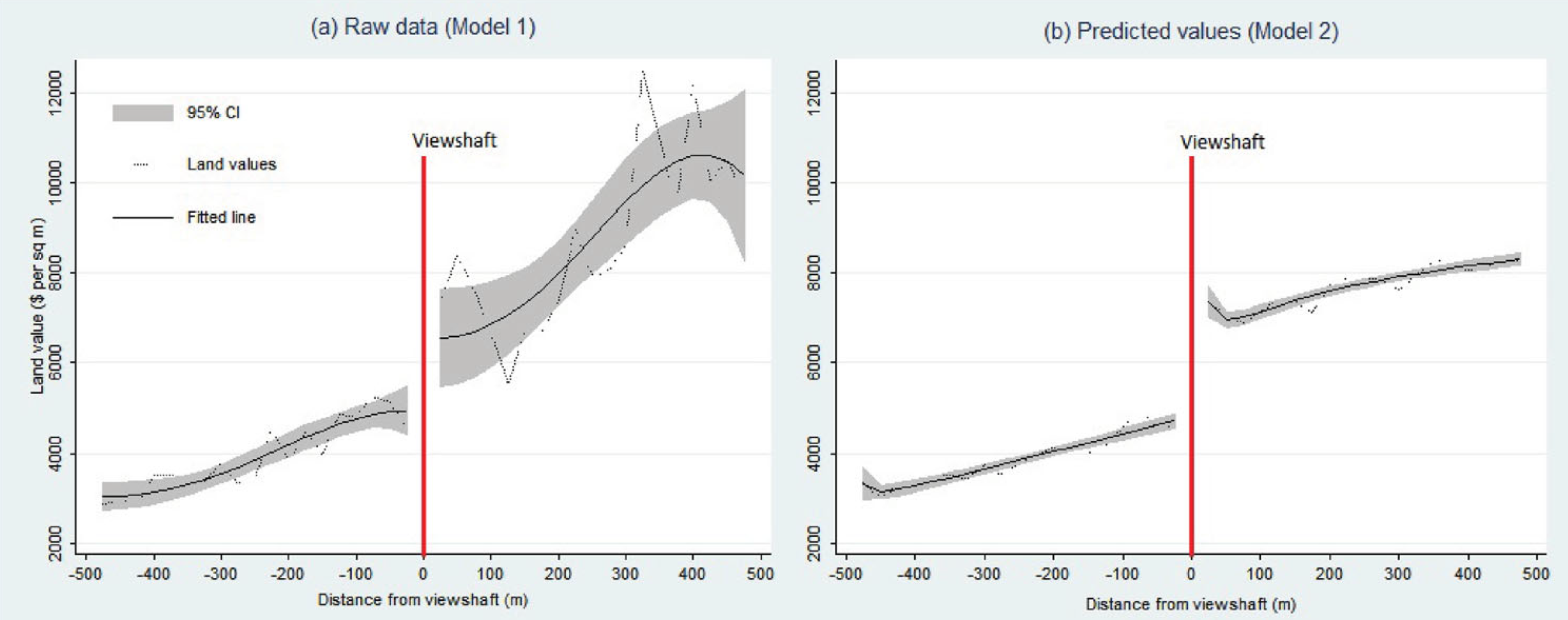

Figure 19 Land values and distance from viewshaft

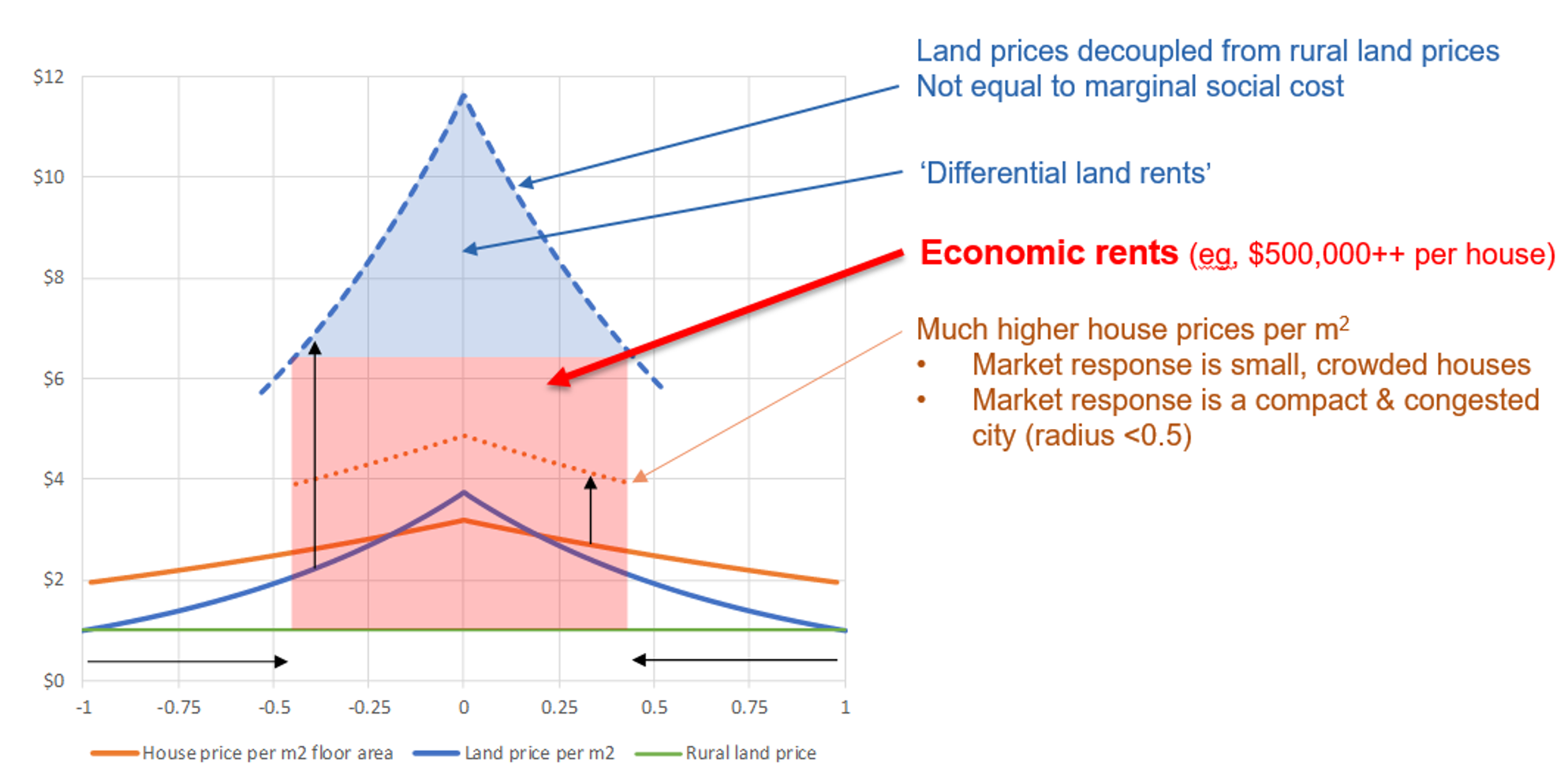

Figure 20 Urban boundary limit leads to an increase in residential land prices

Figure 21 Combined impact of RM system and planning regime

Figure 22 Number of dwellings and land values at distance from CBD over time

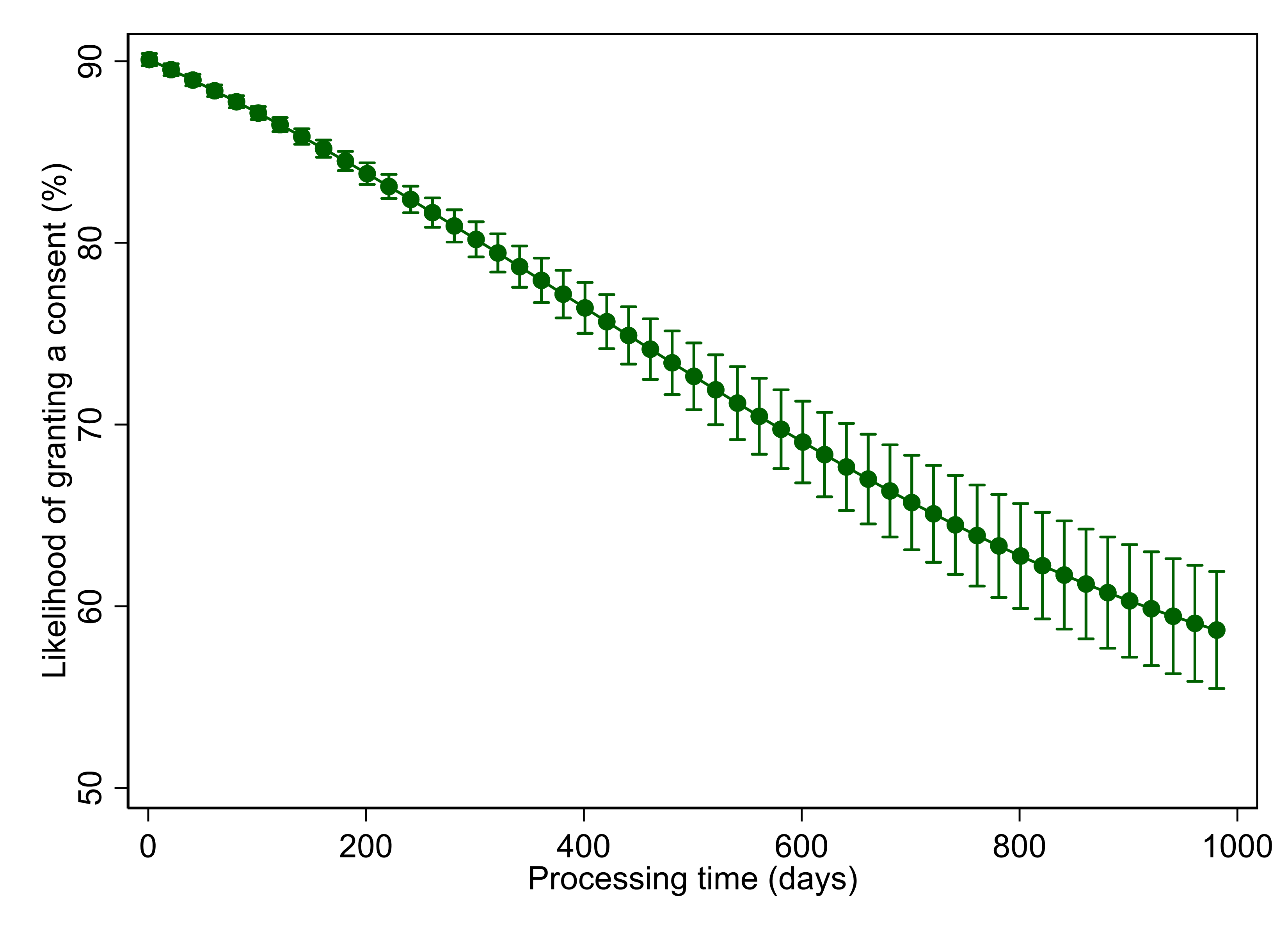

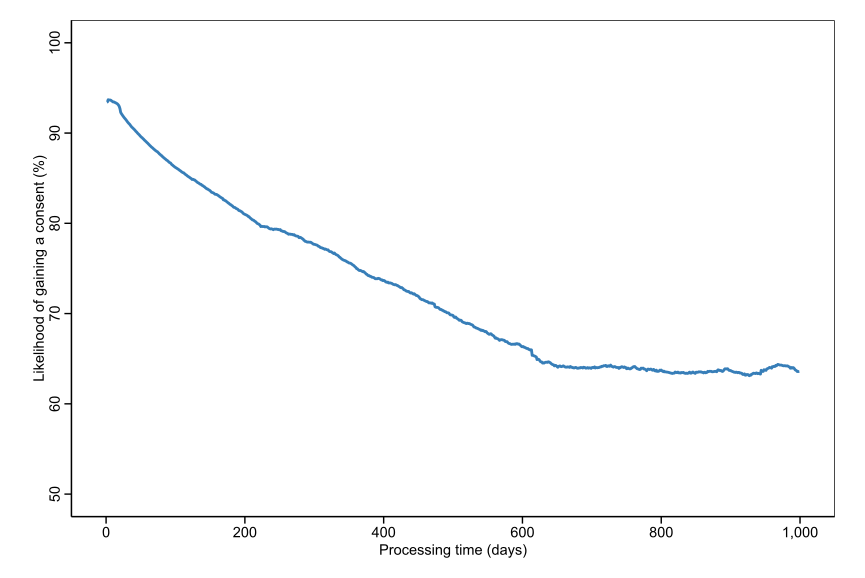

Figure 23 Impact of processing delays on the likelihood of granting a resource consent

Figure 24 Real PPI – Heavy and civil engineering construction

Tables

Table 1 Evaluation of agreement, strength of evidence and overall confidence

Table 2 Housing supply elasticities

Table 3 Difference in land values across the RUB 30

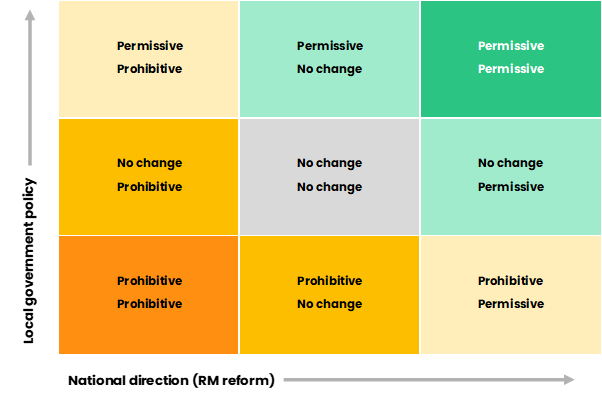

Table 4 High level housing outcomes of NPS-UD and RMA and the RM reform

Table 5 Likely impact of the features of RM system on land values

Table 6 Direction of impact of interest rates on key variables

Table 7 Price response to a 1 percent increase in population

Acronyms

A house price bubble is a period of months or years that speculative purchases lead to increased house prices that cannot be explained based on the factors of supply and demand.

Monetary policy is the actions that the Reserve Bank of New Zealand (RBNZ) takes to influence the money supply, exchange rates, economic activity and inflation. The tool that RBNZ uses is Official Cash Rate (OCR), which is the interest rate for overnight transactions between banks.

Global Financial Crisis (GFC) was a severe global economic crisis between mid-2007 and early 2009.

Resource Management Act 1991 (RMA) is New Zealand’s primary environmental and planning law, covering environmental protection, natural resource management and urban planning.

National Policy Statement on Urban Development (NPS-UD) provides guidelines for improving the competitiveness of urban land markets by increasing the responsiveness of development to local land price changes.

Producer Price Index (PPI) is a price index that measures the average changes in prices received by producers for their output.

Amalgamation refers to the merging of local and regional councils to form the unified Auckland Council in 2010.

Metropolitan Urban Limit (MUL) is a zoning restriction that defines the boundary of the urban area with the rural part of the Auckland region.

Supply elasticity (or supply responsiveness) captures the impact of a 1 percent increase in house prices on the rate of new housing consented. A supply elasticity of between zero and 1 suggests that housing supply is relatively inelastic – i.e., it is not very responsive to an increase in price and house prices are estimated to increase faster than supply, which can be an indicator of shortages and unaffordable housing. An elasticity closer to 0 means that housing supply is less elastic. If elasticity is greater than 1, then housing supply is elastic (response to increases in price).

Viewshaft policy is the planning regulations that regulate development height across urban landscapes to limit development and preserve iconic city views.

1 Introduction

In this report we assess the extent to which the Resource Management Act (RMA) and other environmental regulations have contributed to house price inflation in Aotearoa. To do this, we review the factors of housing price growth (HPG) in New Zealand and provide a simple description of the available data and existing research on the topic. In this chapter, we briefly explain our methodology for the literature review and then present the relevant descriptive statistics for the factors of HPG. Then we have two separate chapters on factors of supply and factors of demand. In each of the chapters we provide different sections on the literature review of the topics of interest. In the last section, we discuss the limitations of the literature and potential future studies required for improving our understanding of the factors of HPG in New Zealand. For the analyses of the factors of HPG, given this project’s short timeframe, we have set limits on the scope of the data analysis. Where information is available, we use the existing work and provide a description of the findings.

1.1 Methodology of literature review

For a systematic review of the literature, we followed a four-step process for finding relevant studies:

Define the topic of interest: For a correct understanding of the drivers of house price growth, we need to have a review of the impact of environmental regulations and all other relevant factors.

Undertake a systematic review of the relevant research literature to the topics of interest. Each factor of demand and supply will be defined as a topic of interest and looked for in the literature in a separate section of our report.

Use independent research search engines and databases, e.g. Econlit, SAGE, SCOPUS, Proquest, Ebsco, Google Scholar, and a general google search for finding the grey literature

Contact relevant New Zealand organisations and authors of relevant research topics to learn about other (unpublished) available sources

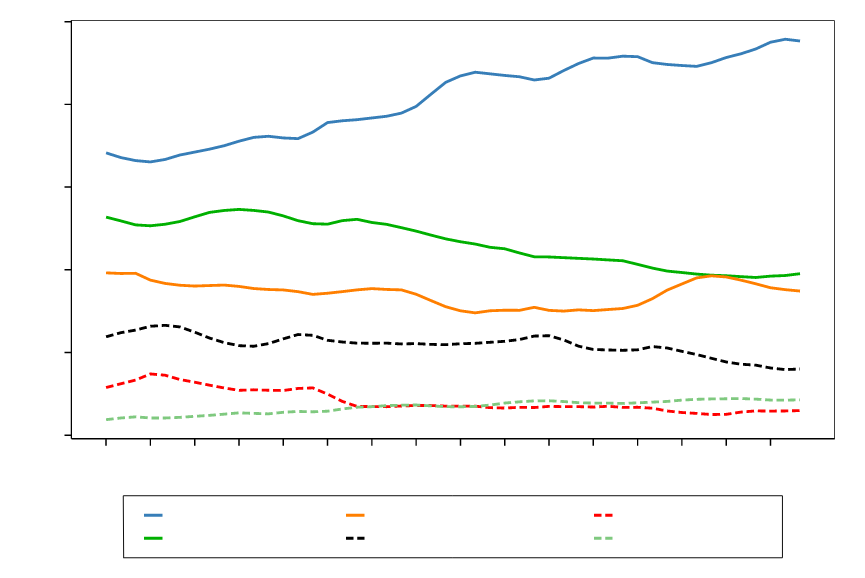

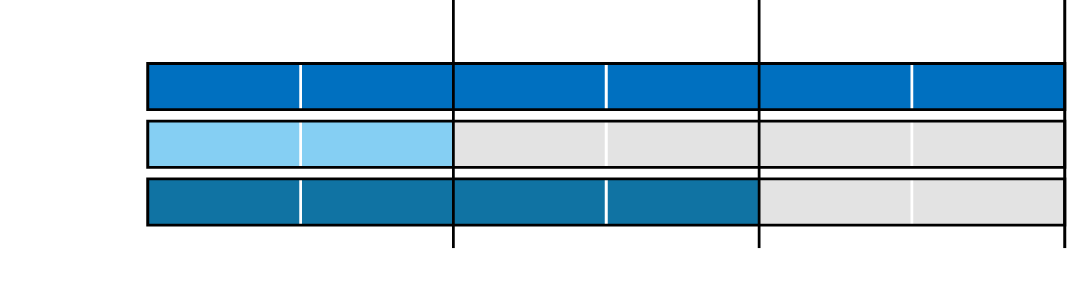

After finding the relevant studies, we assess each chosen topic against the IPCC’s uncertainty framework (IPCC, 2010). To do this, we highlight the methodological quality of the studies (research design). We prioritise using the highest quality well implemented research designs in our review.3 The output of IPCC’s uncertainty framework is illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1 IPCC’s uncertainty framework

Source: IPCC, 2010.

Based on this framework, we rank the agreement, evidence and confidence we have with the results from the literature in a diagram at the beginning of each section. We clarify the hypothesis that the diagram is referring to. ‘Agreement’ shows the level of compliance across the studies on the stated hypothesis. ‘Evidence’ shows the availability and quality of the data and methodology available in the literature on the specific hypothesis. ‘Confidence’ is the combination of agreement, evidence and our evaluation of the credibility of the findings from the literature. The scoring scale used has the following characteristics:

the scale has a range from one to three,

three is the highest score on the scale and one is the lowest,

a score of one would reflect no agreement, no evidence and minimum confidence.

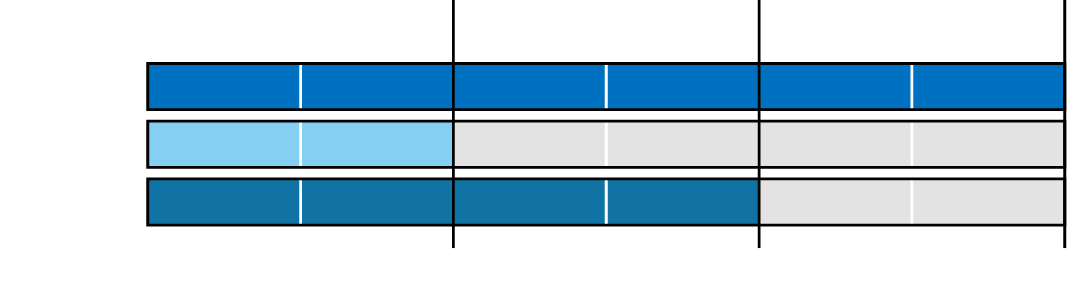

Figure 2 Example of the uncertainty assessment diagram

1.1.0.0.1 Source: Principal Economics.

The topics of interest in this analysis regarding impacts on factors of supply include:

Impacts of (non-environmental) regulations

Impact of environmental regulations

Availability of infrastructure

Supply chains and construction costs

On the demand side factors we include:

Affordability

Monetary policy and mortgage rates

Population and migration

Availability of finance

Household size

Tax policy, housing subsidies and other interventions

In our search for relevant literature, we used a range of keywords to find the available studies from different search engines. Appendix A provides a list of our keywords and the list of the studies that we used by the topic of interest.

1.2 Description of HPG and its factors

HPG has been discussed amongst politicians and academics extensively. Different solutions to housing crises have been proposed over the last decades. The solutions target factors of demand and supply and include increases in deposit ratios, a foreign buyer ban, decreases in zoning regulation, capital gains tax, RM reform amongst the others. The first step to finding a solution is to define the HPG issue correctly and identify its sources. Because of the inter-related impact of the supply and demand factors, one cannot look just at housing supply, or housing demand to judge its impact on housing outcomes. All these aspects must be considered together.4

This section provides a description of the HPG and the related factors using a range of publicly available data. The purpose of this section is to provide some background and motivate the topics of the studies that we review in the next sections. We provide the findings from our review and any causal inference about the impact of different factors of HPG in the next sections. We intend to provide a description of the HPG over the last fifty years for the 1971-2021 period. When data is not available, we illustrate and describe the data for the longest timeframe available.

New Zealand experienced a significant HPG over the last fifty years

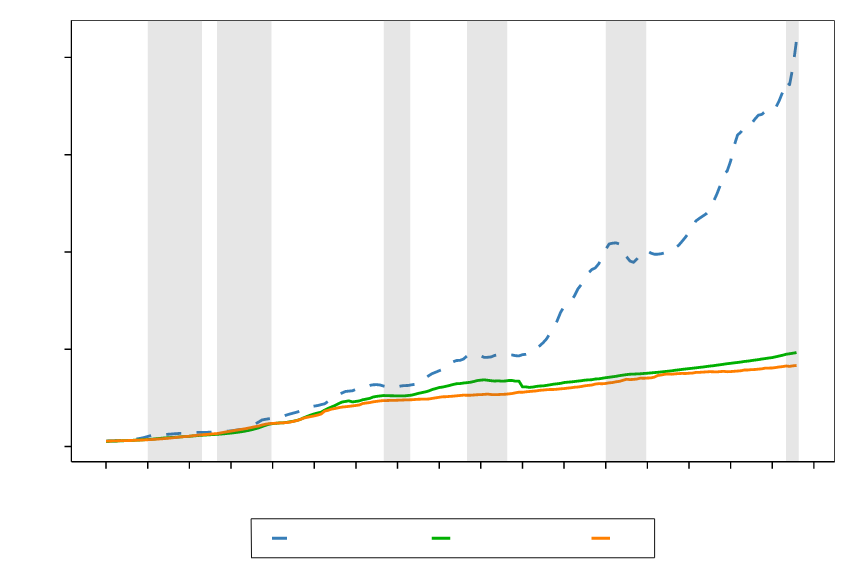

Figure 3 shows the nominal changes in housing prices using a house price index over the 1971-2020 period.5 Nominal house prices are 82.5 times (8251 percent) higher in 2020 than in 1971 (and 342 percent higher in 2020 than in 2001).6 In contrast, over this period, nominal rental prices have grown by around 18.3 times7 and the cost of consumer goods and services has increased 15.7 times based on the CPI.8 The grey shaded areas show a range of major worldwide crises. For most of these crises, the HPG has been small or zero. However, during the Covid-19 pandemic, there has been a significant increase in (nominal) house prices by 34 percent from Jan 2020 – Jun 2021. We describe changes in other factors during these crises in the next figures.

The difference between CPI and the house price index indicates that house price inflation has increased significantly faster than other goods and services. For the balance of this report, we deflate house prices (against the CPI) and present real house price growth in the following paragraphs.

Figure 3 Nominal changes in housing prices

Source: Bank for International Settlements, OECD, Statistics NZ, Principal Economics analysis.

Note: We source seasonally adjusted real property price index from The Bank of International Settlements and adjust to nominal prices using the Statistics NZ CPI, seasonally adjusted rental price index from the OECD and the Statistics NZ CPI. All data is then rebased to 1971 = 100. We highlight notable recessionary periods in New Zealand identified by Reddell et al., (2008). These include the First Oil Price Shock (1974 – 1977), The Second Oil Price Shock (1979 – 1982), The 91 – 92 Recession, (attributable to the 1987 share market crash, subsequent monetary responses and impacts of the first Gulf War - 1991 – 1992), The Asian Crisis and drought (1997 – 1999), we add COVID-19 as an additional recessionary period (2020-).

Over the last fifty years, house prices have grown four times faster than other consumer goods and services

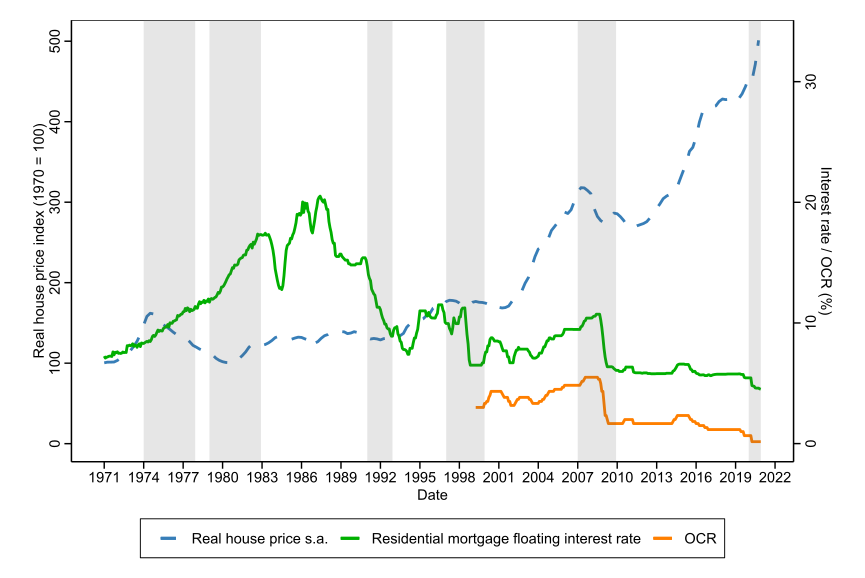

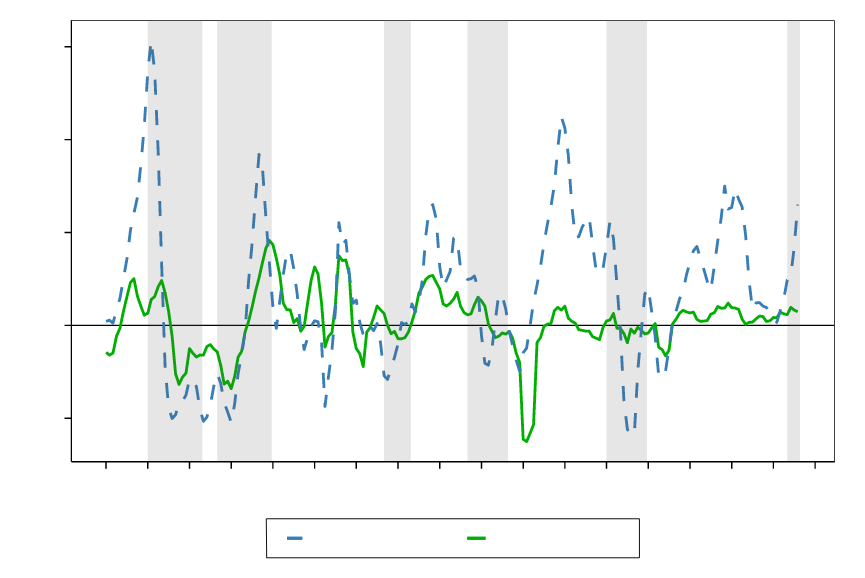

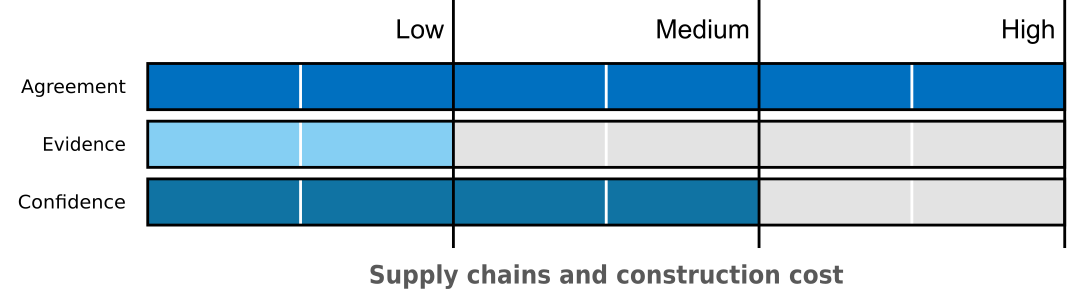

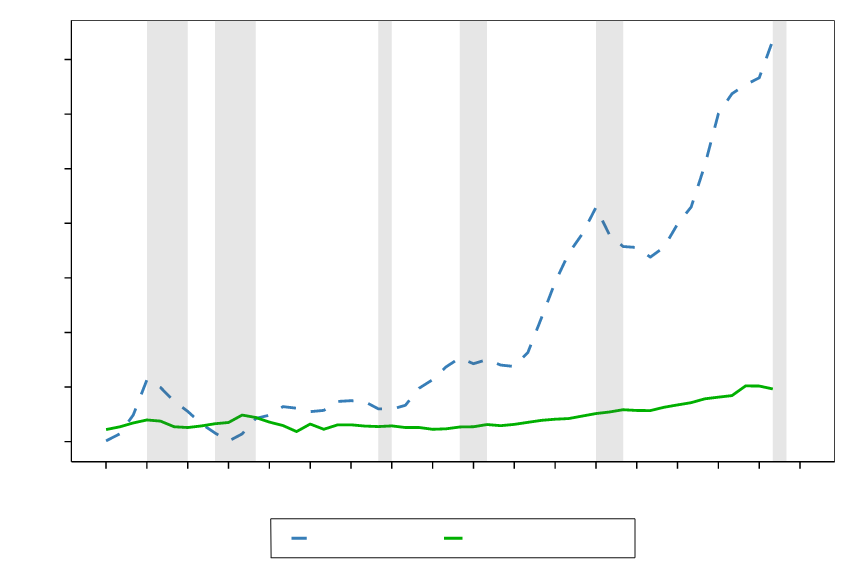

Figure 4 shows the (real) house price growth on the left (vertical) axis and the percentage annual change in residential mortgage floating rate and Official Cash Rate (OCR) on the right axis. The compound average growth rate (CAGR) in house prices over the last fifty years was 3.12 percent and house prices have grown by 364 percent in real terms over this period. This suggests that house prices have grown almost four times faster than other consumer goods and services. The CAGR over the last twenty years (between 2001 and 2020) is 5.23 percent and the real HPG is 176.9 percent. OCR and mortgage rates have decrease significantly over the Covid-19 pandemic period by 0.75 percent.

As will be discussed in the literature review sections, one commonly cited reason for HPG are the low interest rates that have ensued since 1991, enabling greater serviceability of mortgages and higher borrowing potential. As shown in Figure 4, over the 1971-2021 period, mortgage floating rates have been extremely volatile with a minimum of 4.51 percent in December 2020 and a maximum of 20.5 percent in June 1987.

Figure 4 House price growth and residential floating mortgage interest rates

Source: Bank of International Settlements, RBNZ (years 2004 – 2021), Te Ara (years 1966 – 2008), Stroombergen, (2010), Principal Economics analysis.

Note: We source historic variable first-mortgage housing rate (1966 – 2008) from Stroombergen, (2010) and append the residential mortgage floating interest rates from RBNZ, opting for RBNZ data for overlapping years. Similarly, the OCR has been sourced from the RBNZ. We discuss the source and adjustments to made for real house price s.a. series earlier this report in Figure 7. We rebase the real property price index sourced from The Bank of International Settlements to 1971. We highlight notable recessionary periods in New Zealand identified by Reddell et al., (2008). These include the First Oil Price Shock (1974 – 1977), The Second Oil Price Shock (1979 – 1982), The 91 – 92 Recession, (attributable to the 1987 share market crash, subsequent monetary responses and impacts of the first Gulf War - 1991 – 1992), The Asian Crisis and drought (1997 – 1999), we add COVID-19 as an additional recessionary period (2020-).

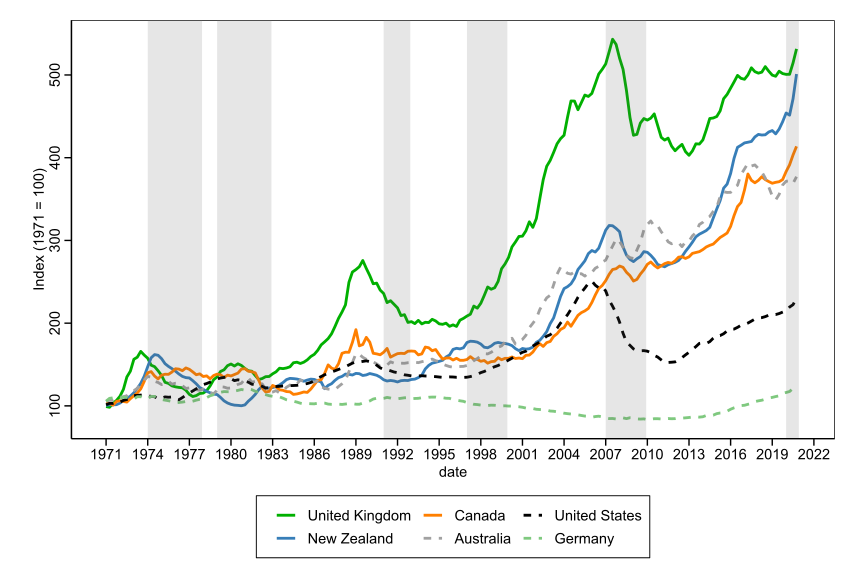

New Zealand HPG has been the highest during the Covid-19 pandemic

Figure 5 illustrates the changes in real house prices for New Zealand and other countries. Over the 1971-2021 period, the HPG in New Zealand has been the second highest, with slightly slower growth than the UK. The response of different housing markets to crises has been different. For example, the GFC led to significant price decreases in the US and the UK, with smaller increases in New Zealand and Germany, and raised house prices in Australia and Canada. This partly reflects the impact of local monetary policy and the availability of finance to appropriately respond to a short-term economic crisis. During the Covid-19 pandemic, most countries have experienced increases in house prices, partly due to lower mortgage rates. During this period, New Zealand has the highest HPG amongst the listed countries, which may indicate the impact of lower mortgage rates combined with the shortage of housing evident from the already increasing house price trend before the Covid-19 period.

Figure 5 International changes in real house price

Source: Bank for International Settlements

Note: We source seasonally adjusted real property price index from The Bank of International Settlements. All data is rebased to 1971 = 100. We highlight notable recessionary periods in New Zealand identified by Reddell et al., (2008). These include the First Oil Price Shock (1974 – 1977), The Second Oil Price Shock (1979 – 1982), The 91 – 92 Recession, (attributable to the 1987 share market crash, subsequent monetary responses and impacts of the first Gulf War - 1991 – 1992), The Asian Crisis and drought (1997 – 1999), we add COVID-19 as an additional recessionary period (2020-).

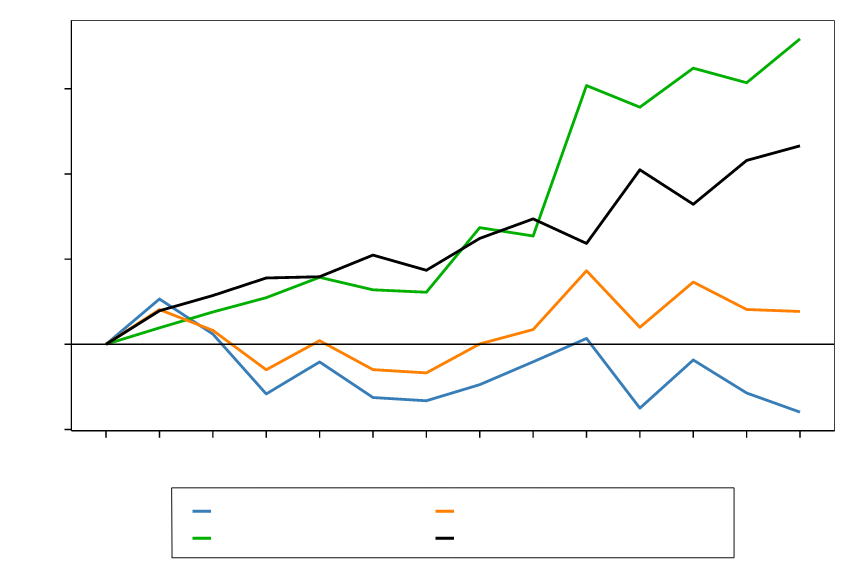

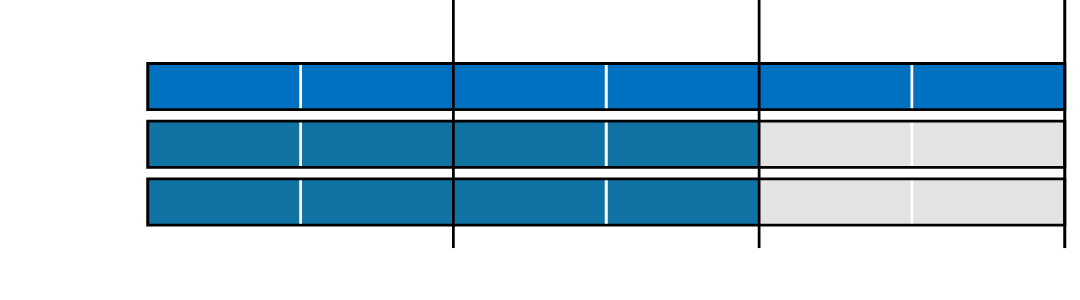

Over the last decade, the cost of housing consumption has increased more significantly for renters

Figure 6 shows how real housing costs for renters and owners since 2007. Total mortgage payments have increased slower than the rent payments. The principal payments have increased more significantly than rents. his is driven by increased house prices. The mortgage interest rates have decreased as a result of progressively lower interest rates. The higher increase in cost of renting compared to homeownership has potentially led to increased demand and higher HPG over the last decade.

Figure 6 Real housing cost indices

Source: Statistics NZ, Principal Economics analysis.

Note: We source household expenditures on housing from the Statis NZ Household Economic Survey and construct an index for each expenditure type. This is then deflated by the CPI to determine the real housing cost price indices shown in the figure. We highlight notable recessionary periods in New Zealand identified by Reddell et al., (2008). These include the First Oil Price Shock (1974 – 1977), The Second Oil Price Shock (1979 – 1982), The 91 – 92 Recession, (attributable to the 1987 share market crash, subsequent monetary responses and impacts of the first Gulf War - 1991 – 1992), The Asian Crisis and drought (1997 – 1999), we add COVID-19 as an additional recessionary period (2020-).

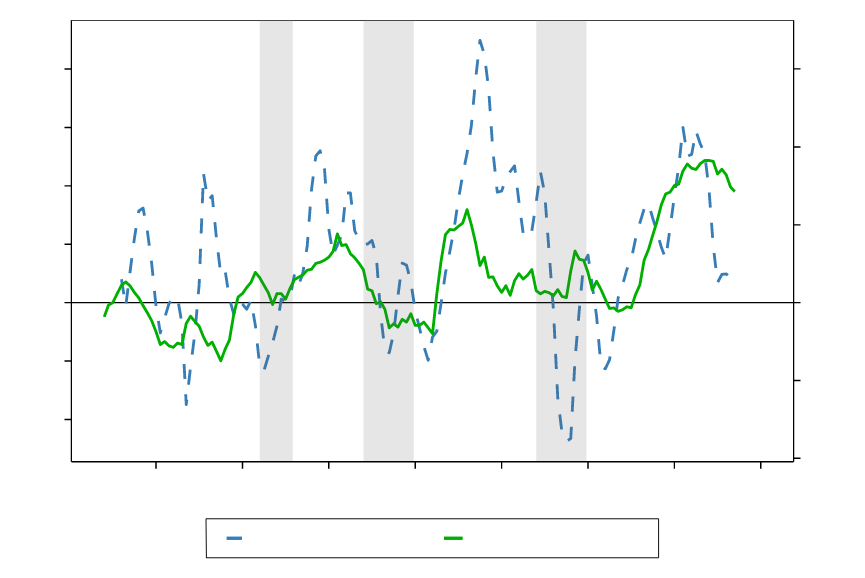

The cost of housing consumption, however, has not increased nearly as high as house prices

Figure 7 illustrates the seasonally adjusted (s.a.) residential rental price over the 1971(Q1)-2020(Q4) period. The 19.4 percent rise in real rental prices suggests that the cost of housing consumption has grown faster compared to other consumers good and services over the last fifty years. The rate of real rental prices growth (19.4 percent) is, however, significantly lower than that of real house prices (364 percent). The relatively high HPG compared to growth in cost of renting may be an indicator for high speculation incentives. The “Bright-Line” test is a tax instrument for addressing potential speculative behaviour. We discuss the potential impact of the tax policy and “Bright-Line” test in section 3.6.

Figure 7 Residential rental prices

Source: Bank for International Settlements, OECD, Statistics NZ, Principal Economics 2021 analysis.

Note: We source s.a. real property price index from The Bank of International Settlements, s.a. rental price index from the OECD and Statistics NZ CPI. We rebased all indices to 1971, deflate s.a. rental price index using the CPI and calculate the quarterly year-on-year change for relevant series shown in Figure 7. We highlight notable recessionary periods in New Zealand identified by Reddell et al., (2008). These include the First Oil Price Shock (1974 – 1977), The Second Oil Price Shock (1979 – 1982), The 91 – 92 Recession, (attributable to the 1987 share market crash, subsequent monetary responses and impacts of the first Gulf War - 1991 – 1992), The Asian Crisis and drought (1997 – 1999), we add COVID-19 as an additional recessionary period (2020-).

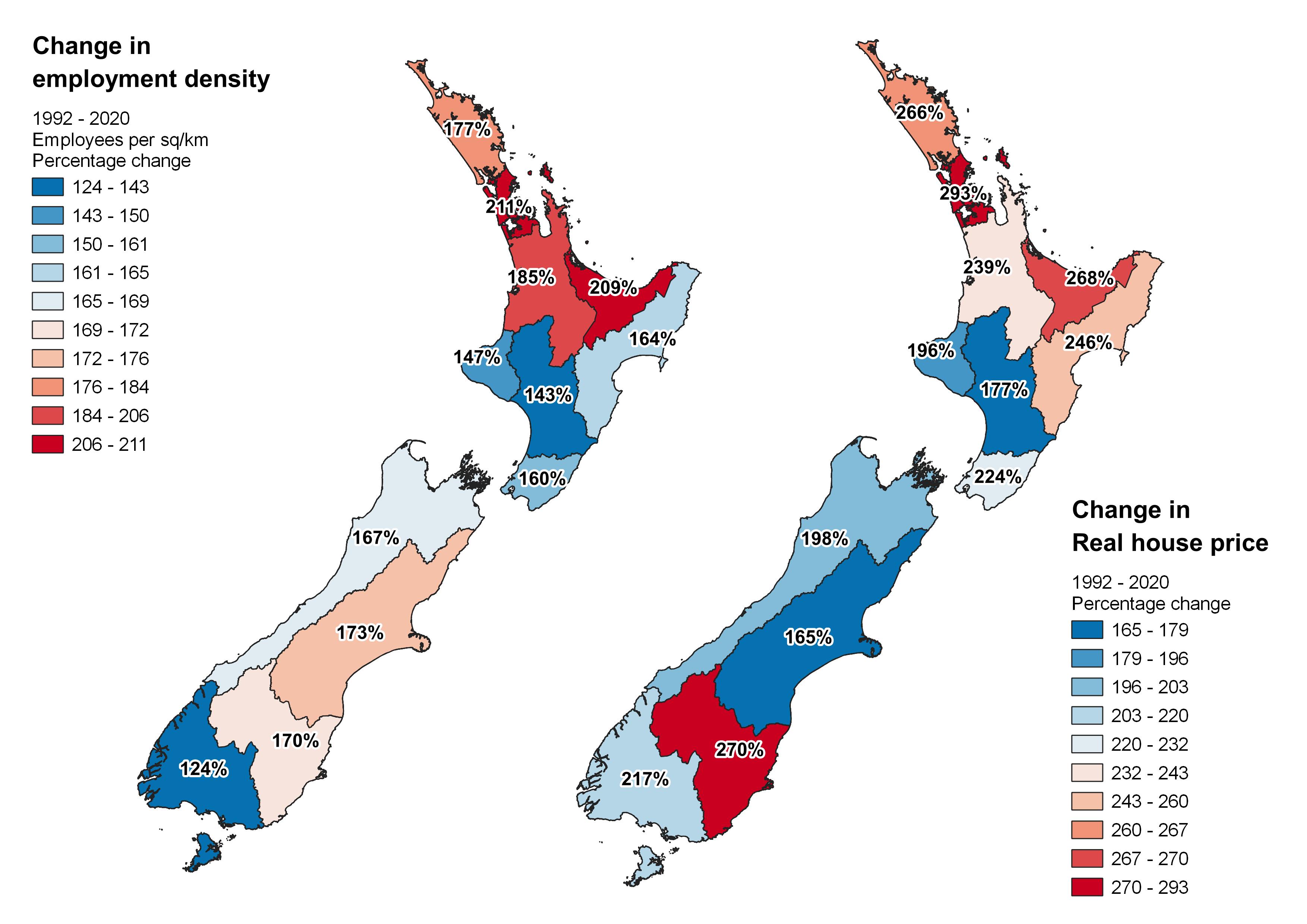

Regions with increased employment opportunities have experienced higher HPG

As shown in the left hand side in Figure 8, between 1992 and 2020,employment density across New Zealand regions grew with significant higher densities in large urban areas, more than doubling in the regions of Auckland (211 percent) and Bay of Plenty (209 percent).These regions have also experienced some of the highest growth in real house prices over the same period with 293 and 268 percent house price growth, respectively – as shown on the right map. The high house price growth associated with high employment opportunities may be an indication of the positive association between international (and local) migration and HPG. While there is a positive correlation between HPG and the growth in employment density, the ratio of the two growth series varies significantly across regions, which suggests the importance of the impact of other related factors on HPG. We review the impact of population growth on HPG in section 3.3.

Figure 8 Growth in employment density and real house prices

Source: REINZ, Statistics NZ, Principal Economics analysis.

Note: We use employment data from the Statistics NZ Household Labour Force survey and calculate the employment densities using regional land areas reported in Statistics NZ geographic boundaries files. We amalgamate areas to match those reported by REINZ for house prices to allow for comparisons. We source house prices from REINZ and deflate the reported data for inflation using the Statistics NZ CPI before calculating house price growth.

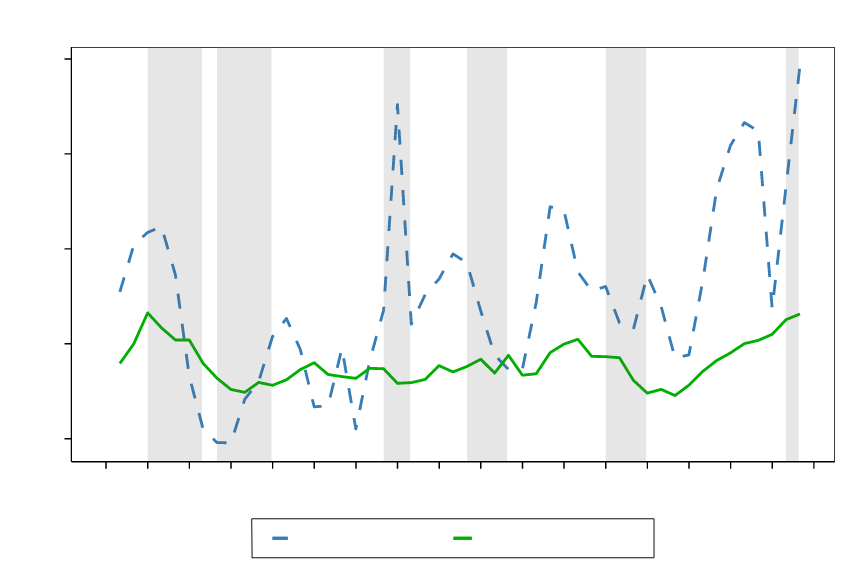

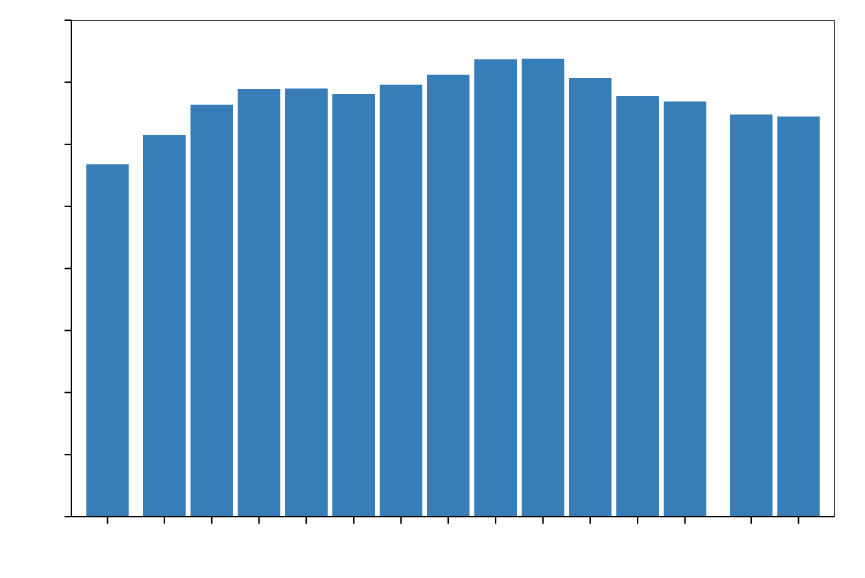

The population growth outpaced the housing supply

The supply of housing has not grown proportionately to the growth of population. Figure 9 shows that the numbers of new building consents across New Zealand have grown by 66 percent, while growth in population has been 75 percent over the 1971(Q1) – 2020(Q4) period. As will be discussed in section 3.4, the gap between demand and supply has further widened because of the decrease in the size of New Zealand households, which requires more dwellings to be supplied. We review the factors of this stringent housing supply in section 2.

Figure 9 Building consents and population growth

Source: Statistics NZ, Data 1850, Principal Economics analysis.

Note: We source our annual population data up to 2017 from Data 1850 and append additional years from Statistics NZ and determine the annual change. We use monthly new residential building consents data from Statistics NZ and aggregate by calendar year. We highlight notable recessionary periods in New Zealand identified by Reddell et al., (2008). These include the First Oil Price Shock (1974 – 1977), The Second Oil Price Shock (1979 – 1982), The 91 – 92 Recession, (attributable to the 1987 share market crash, subsequent monetary responses and impacts of the first Gulf War - 1991 – 1992), The Asian Crisis and drought (1997 – 1999), we add COVID-19 as an additional recessionary period (2020-).

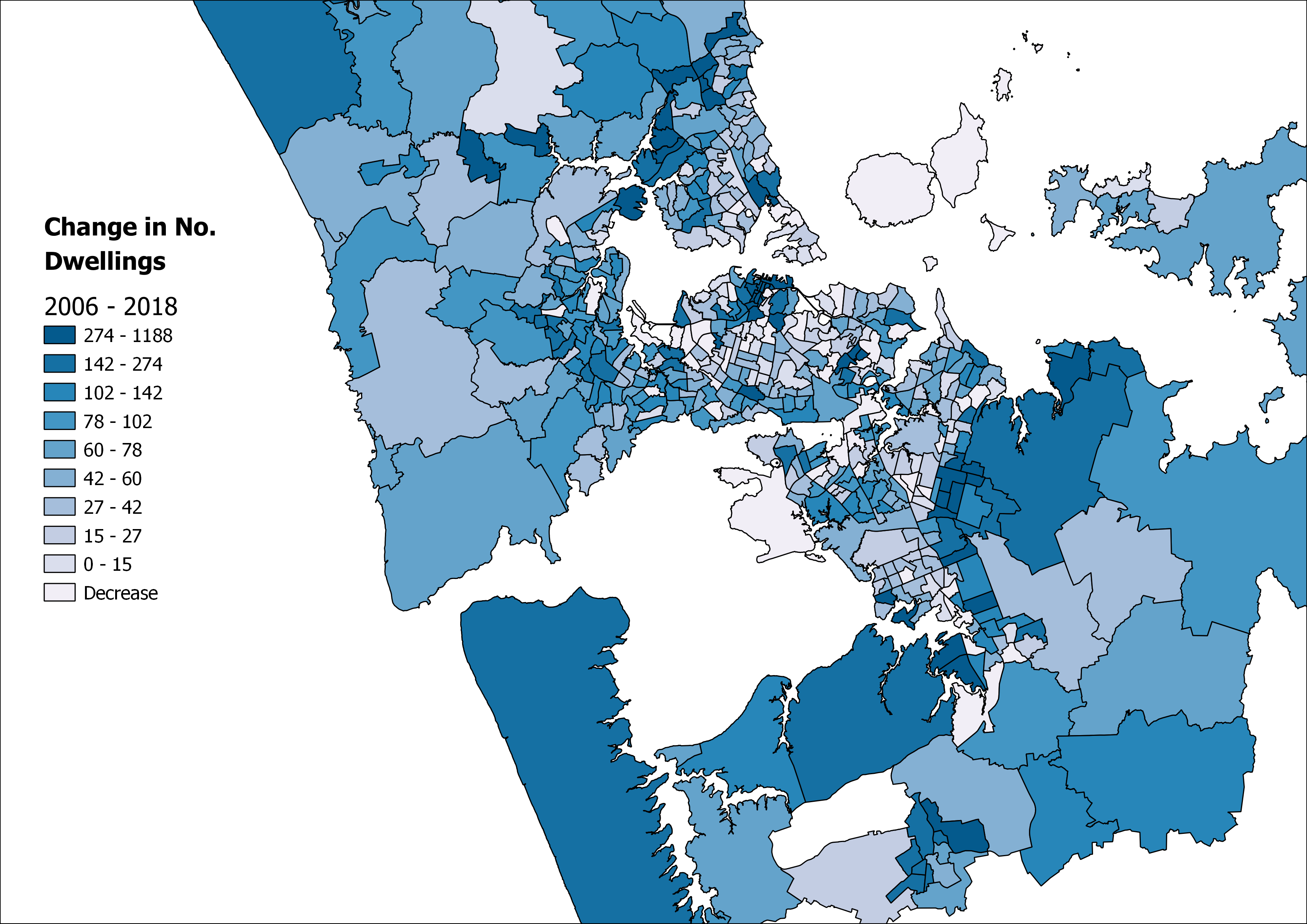

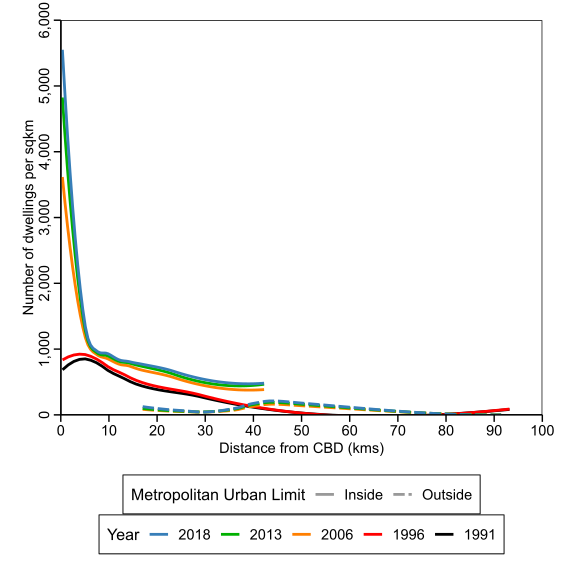

Planning regulations limited urban growth and led to a less responsive housing supply

In the absence of other costs, a higher HPG usually leads to increased incentives for the construction sector to supply more housing. However, the supply of housing has not been responsive to HPG in New Zealand - as will be discussed in Section 2. Using Auckland as an example, Figure 10 shows that growth in the number of dwellings has occurred mostly in the CBD and limited areas on the periphery of the city.9 This is an indication of the impact of regulation that has limited both brownfield and greenfield urban growth opportunities. (Cooper & Namit, 2021; Lees, 2017, 2019; Martin & Norman, 2020; Norman et al., 2021; Parker, 2021; Torshizian, 2016)

Investment in housing has grown at a faster rate than any other asset

Figure 11 shows the proportion of net capital stock (replacement value) across each asset type over the years of 1972-2019 with residential building increasing from 34 percent to 48 percent of total capital stock. Bassett et al. (2013) suggest this represents a “drag on New Zealand’s investment patterns” with investment in more productive sectors losing out to the housing market. We review the literature on the impact of the availability of finances in section 3.5.

The wide range of regulatory changes over the last century has constantly affected the housing market

Based on the literature, there has been a wide range of Acts, reforms and legislations that have affected the housing market in the last century. As shown in Figure 12, notable regulations including the RMA and the Building Act of 2004 follow earlier regulations in the housing market landscape. As will be discussed in our review of the literature, because of the inter-related impacts of these regulatory frameworks, our understanding of the impact of each regulation on HPG is limited.

1.3 HPG and housing affordability

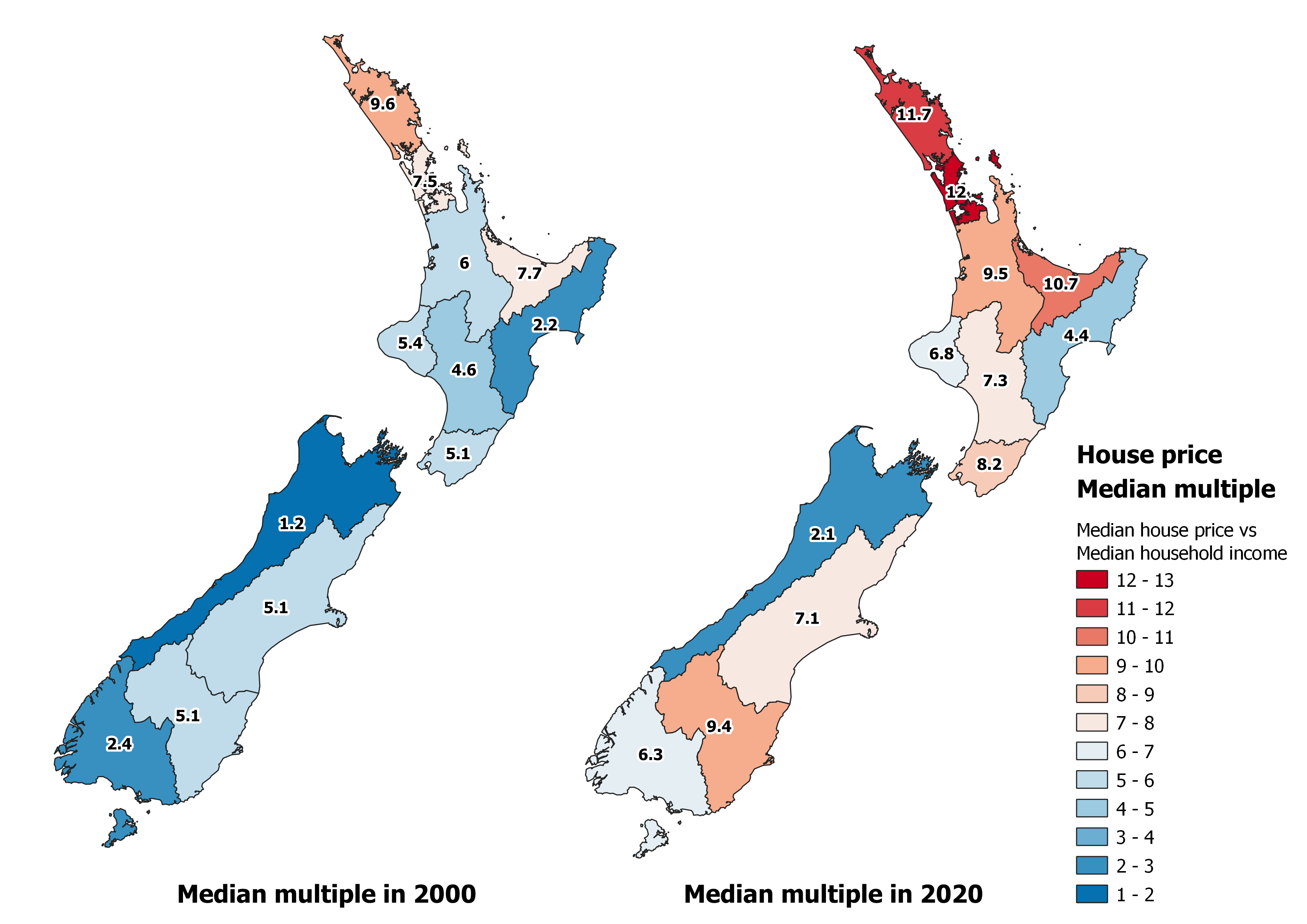

The significant HPG has led to a lower housing affordability across all regions and most significantly in Auckland.

Simple measures such as the median-income house-price multiple shown in Figure 13 can provide an indicator for housing affordability. Accordingly, the median price to income multiplier in Auckland has increased from 7.5 in 2000 to 12 in 2020. While indicators tend to be blunt tools for describing affordability, an increase in the ratio of median house price to income from 6.02 to 9.74 for New Zealand is a significant sign of increasing housing affordability issues. We review housing affordability and its factors in section 3.1.

Figure 13 House price to household income median multiple10

Source: REINZ, Statistics NZ, Principal Economics analysis.

Note: We source weekly household median wage and salary incomes from the Statistics NZ Household Labour force survey. Median house prices have been sourced the REINZ. In order to calculate the median multiple in each area and year we harmonize the datasets from REINZ and Statistics NZ by taking the average, median house price for the relevant years and areas (where areas are reported differently between sources) and calculate the stratified average household income based on household counts to determine household incomes. Our weekly estimates are then converted to annual based on a 52-week year.

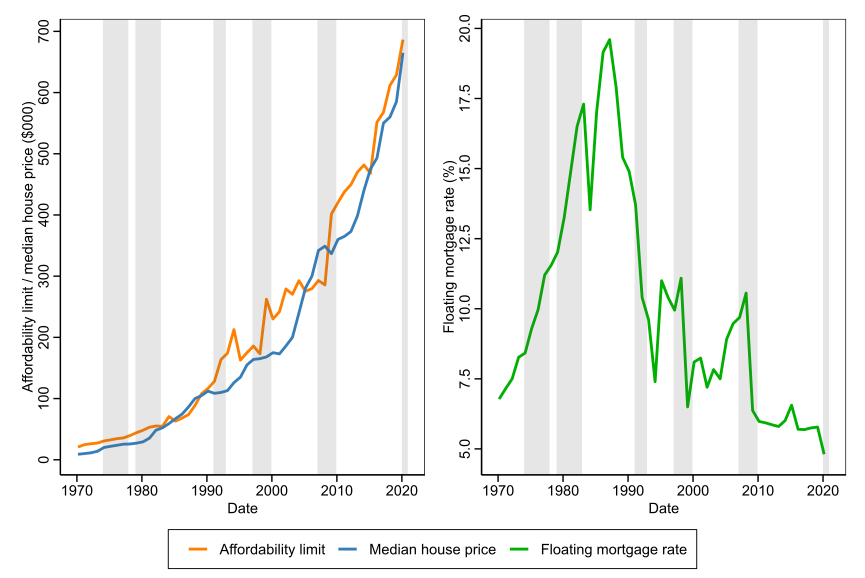

The price that the median household income group could afford to pay has increased significantly over the last fifty years

The price that a household can afford to pay is a function of a range of factors, including changes in mortgage rates and household income.11 We used our housing affordability simulation model (ASIM) to show the changes in household affordability of the median household income group over the 1970-2020 period.12 As illustrated, there is a strong positive correlation between the amount that households can afford to pay and the median house price. While the mortgage rates have increased significantly up to 1986, the significant rise in income contributed to higher housing affordability levels. We review the relevant literature in sections 3.1 and 3.2.

Figure 14 Housing affordability/mortgage serviceability over time

Source: Statistics NZ, Bank for International Settlements, REINZ, RBNZ, Te Ara (years 1966 – 2008), Stroombergen, (2010), Principal Economics analysis.

Note:We estimate the Affordability Limit for the median households in New Zealandusing an adjusted multiplier (AM) which isthe maximum affordable loan to income ratio given the interest rate(i), the down-payment ratio (β), term of the loanandthe proportion of income a household allocates to mortgage payments(α). The formula we use for determining the adjusted multiplier is shown below.

\[AM = R \times \left( \frac{{1 - \left( 1 + i \right)}^{- N}}{i} \right),R = \frac{\propto}{1 - \beta}\]

We assume a down-payment ratio of 5%, 25-year loan term and 50% income to mortgage payment ratio across all periods to determine the Affordability limit shown in Figure 14. Median household incomes house prices have been sourced from Statistics NZ Household Labour force survey for the years of 1998 – 2020, which we backdate to 1970 using the average weekly income index. While this is an imperfect estimate given differences in household composition over time, it provides a reasonable long-run estimate of household incomes levels given the data available. We source historic variable first-mortgage housing rate (1966 – 2008) from Stroombergen, (2010) and append the residential mortgage floating interest rates from RBNZ, opting for RBNZ data for overlapping years. We rebase the real property price index sourced from The Bank of International Settlements to 1971. We highlight notable recessionary periods in New Zealand identified by Reddell et al., (2008). These include the First Oil Price Shock (1974 – 1977), The Second Oil Price Shock (1979 – 1982), The 91 – 92 Recession, (attributable to the 1987 share market crash, subsequent monetary responses and impacts of the first Gulf War - 1991 – 1992), The Asian Crisis and drought (1997 – 1999), we add COVID-19 as an additional recessionary period (2020-).

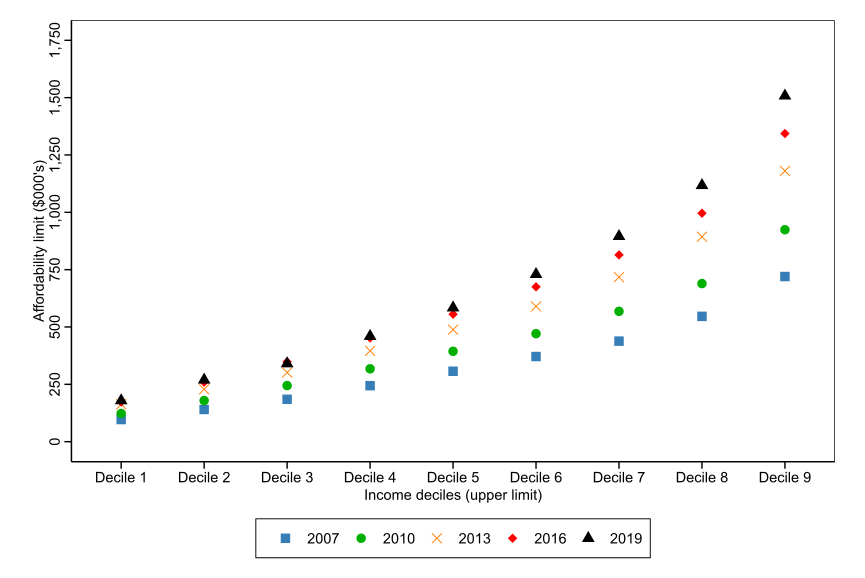

The gap between affordability levels of the highest and lowest income groups has widened

Figure 15 shows the price that each household income group can afford to pay for purchasing a house. We have assumed that the proportion of income allocated for homeownership is fixed at 50 percent. Accordingly, the affordability for higher income deciles has increased at a faster rate over the years of 2007 – 2019. Affordability limits for the decile 9 household income group has increased by 23 percentage points higher than decile 1.

Figure 15 Housing affordability/mortgage serviceability at different income levels

Source: Statistics NZ, RBNZ, Principal Economics analysis.

Note: We estimate the affordability limits by year and income decile as categorised in the Statistics NZ Household Economic Survey. Affordability limits are determined using the formula noted in Figure 14 using the upper income limits for each decile group and the 2-year fixed mortgage interest rate.

The high HPG, increased affordability limits and higher rental prices relative to mortgage payments have led to lower homeownership over the last two decades

As shown in Figure 16, in 1971, 64.5 percent of households owned their own home, with this proportion peaking in 1991 at 73.8 percent. Home ownership has since gradually declined to 64.5 percent in 2018. The year 1991 is significant as it has marked the end of the home-ownership support programmes and the start of a significant sell-off of state housing in New Zealand (Johnson et al., 2018). Over the period 1991 – 1999, state housing stock decreased by 8,900 units or 13 percent of the total state housing stock (Schrader, 2012).

2 Impact of the factors of supply

When there is no scarcity of housing, the market is competitive and there is no reason for the existence of any price premium on a property.13 In a competitive market, all demand will be met with a supply. Around the world, there are cities with relatively high responsiveness of housing supply. In New Zealand, however, many studies estimate significant impacts from housing supply rigidities on housing supply and prices. For example, while the supply elasticity of New Zealand is estimated at 0.7114, the cities across the United States, with similar population density levels, have a supply responsiveness factor (supply elasticity) of 2.15

As presented in Figure 17, in response to increases in population, a rigid supply provides less housing (gross floor areas) and leads to higher house prices. As PwC (2020) discusses, the impact of supply rigidities is magnified during periods of faster population growth. PwC (2020) suggests that improving competitiveness in the land market such that the supplier of land and the consumers can compete across space and land uses, can lead to a less rigid housing supply.

Figure 17 Impact of rigid supply on house prices

Source: PWC, 2020.

ANZ Research (2020) reflected on the supply issues; and discussed the existence of an infrastructure deficit and a significant housing shortage of between 60 and 120 thousand homes. They cited the scarcity of buildable land as an increasing problem, due to planning and zoning restrictions, land banking, urban-drift, poor infrastructure provision and other land-use pressures. We review the literature and discuss these factors further in the next sections.

There has been extensive literature on the impacts of factors of supply on house prices. Factors of supply have been discussed more thoroughly compared to the demand factors. There are multiple reasons that may have contributed to this:16

Most factors with direct impact on HPG are driven by the central and local government regulations. Most factors of demand have wider implications for the economy, with difficulties in measuring their impacts on HPG

Technically, capturing the impact of supply factors is relatively easier than capturing the impact of demand factors (given their wider implications for the economy)

There is a potential tendency for academic economists to replicate the work of their international peers, which is more focused on the factors of supply.

The lower responsiveness of housing supply (to a 1 percent increase in house prices) over time is an indication of the costly (restrictive) planning regulations

Grimes (2007) used a model (based on Tobin’s “q” approach17) to test the determinants of new housing supply. His results suggest that an increase in house prices by 1 percent (relative to total development costs) increases the new housing supply by a factor of between 0.5 and 1.1 percent.

We have listed the housing supply elasticity estimates available from the literature in Table 2. They capture the impact of a 1 percent increase in real house prices on the rate of new housing consented.18 Given this and the period of data coverage, the highest and lowest estimate of supply elasticities estimated in most of these studies provide information about the potential impact of planning policy within the RMA regulations.

The regional estimates using most recent data for Auckland, Hamilton, Tauranga, Christchurch and Queenstown suggest a decrease in the supply response to an increase in house prices over time.19 The reason for this decrease in supply elasticity can be geographic constraints, planning regulations, and technical constraints in the construction market (MRCagney et al., 2016; Saiz, 2010). We discuss this further in the next section.

Table 2 Housing supply elasticities

| Author | Auckland | Hamilton | Tauranga | Wellington | Christchurch | Queenstown |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sanchez and Johansson (2011) Nation-wide model (1994 -2007), Quarterly data | 0.705 | 0.705 | 0.705 | 0.705 | 0.705 | 0.705 |

| Grimes and Aitken (2010) TLA level (1991 -2004), Quarterly data | 1.000 | 2.900 | 1.200 | 0.200 | 1.100 | 3.600 |

| Grimes and Aitken (2006) National average (1981-2004) | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 |

| (Hyslop et al., 2019) | 1.200 | 1.200 | 1.200 | 1.200 | 1.200 | 1.200 |

| PwC (2020) TLA level (1998 -2019), Monthly data | 0.876 | 0.840 | 0.517 | 1.353 | 0.778 | 0.875 |

Source: Sanchez and Johansson (2011); Grimes and Aitken (2010); Grimes and Aitken (2006); Hyslop et al., 2019; PwC, (2020).

2.0.0.1 The minimum cost of an irresponsive housing supply to the New Zealand economy is equal to 0.39 percent of its GDP ($1.3 billion per annum)

Nunns (2019) studied the socioeconomic impacts of rising house prices in New Zealand.20 His results suggest that a comprehensive removal of the housing supply constraint in New Zealand, with no trans-Tasman migration, will lead to an increase in per worker output by 0.8 percent (we review this study in more details in section 3.3). As the author mentioned, the study provides an indicative figure for the potential cost of a rigid housing supply. The lower land prices should be associated with allocation of capital (from other sectors of the economy) to lead to an increase in housing supply. This reallocation of the resources and the interaction between the housing sector (primarily the construction sector) and the other sectors of the economy needs to be investigated in a future study.21

To estimate the economic impact of the existing supply constraint, we used Nunns' (2019) estimate of the output per worker impact as an input to Principal Economics’ Computational General Equilibrium (CGE) Model. Our high-level estimate suggests that the annual cost of the supply rigidity in New Zealand is around 0.39 percent of its GDP.22 This is in absence of a potential increase in immigration to New Zealand as a result of a lower cost of housing.

2.1 Impact of regulations

Description

Regulation is the main tool of local and central governments affecting house prices.23 In theory, a more permissive regulatory regime increases competition amongst landowners, and is associated with a lower (or zero) speculation opportunities and lower house prices. Therefore, to reach a competitive land market has been the focus of the NPS-UD (2020).

In practice, the impact of regulatory barriers, institutional inefficiencies, and uncertainties associated with regulations are closely inter-related. Technically, the land price measure consists of elements of both costs and benefits of regulation. A higher price may be an indication of the benefits of councils’ services, such as improved access to amenities and facilities, or the costs imposed by inefficient regulations.

Summary of literature review

As we review in this section, several economic studies of the impact of regulation, provide estimates of the costs of regulation but there are relatively few studies that have examined the benefits of regulation. For example, there are many studies trying to estimate the costs of urban limit regulations, but there is no study identified of the potential benefits of urban limit regulation (through decreased negative externalities from urban growth on neighbouring regions). This is potentially because regulation is associated with difficult-to-quantify (social) benefits. Based on the literature, we know that a market-driven housing market, with minimal regulations, leads to lower house prices24 but it might have higher costs not expressed in the market.

From the available literature, it is not clear if the available resources in the economy, including capital, labour and technology required for construction of new houses, will be able to provide the size and magnitude of housing required for a flexible housing supply at a reasonable price.

Uncertainty assessment: restrictive regulation has led to higher house prices.

Lees (2019) assessed the cost of land use regulations using four different methods (inspired by Glaeser & Gyourko (2003). For this analysis he used detailed unit record house sales data sourced from Auckland Council and CoreLogic, with coverage for the 2012-2016 period. After accounting for a range of factors, including financing and council fees, his results suggest that house prices significantly exceed construction costs and that the price to cost ratios have increased over time. For example, between 2012 and 2016, the price to cost ratio in Auckland has increased from 2.72 to 3.37. During the same period, the ratio for apartments has increased from 2.62 in 2012 to 3.5 in 2016. His results for Christchurch and Queenstown are similar to Auckland. Lees (2019) concluded that the supply has not been responsive to prices.25 Using the same data and methodology, Lees (2019) estimated the cost of regulation in Auckland can be up to 56 percent of the cost of an average dwelling. Figure 18 shows his estimates of the cost of land use regulation.26 Lees (2019) discusses that the estimated cost of land use regulation could capture anything that drives a wedge between prices and construction costs, including the costs imposed by planning regulations and potential costs imposed from geographic restrictions, such as steep terrain in parts of Wellington and Queenstown. However, Lees (2019) argues that the likelihood of geographic restrictions being the driver of the price margin is low.27

Figure 18 Land regulation costs

Source: Lees (2017).

A more competitive land market will increase competition between locations across a city and across different land uses. The decrease in the market power of landowners decreases land values. To achieve this, it is required that local governments promote development permission for both brownfield and greenfield developments, particularly in areas of high demand with better access to jobs. The results of a recent study by the Chief Economist Unit of Auckland Council confirm that more up-zoning (i.e. allowing greater housing density) is required to accommodate for the demand in areas closer to the city centre (Norman et al., 2021). The study does not account for the costs of supply in different locations.

In a comprehensive study of the costs and benefits of the NPS-UD, PwC (2020) estimated direct and indirect impacts of intensification, minimum car parking requirements, and local government’s strategic planning requirements. Their results suggest that the benefit to cost ratio (BCR) of achieving higher responsive housing supply (to price changes) across New Zealand cities is between four and seven.28

MRCagney et al. (2016) provides a comprehensive cost benefit analysis for policy options for the NPS-UDC. They investigated the impact of planning constraints including general zoning restrictions, MUL, building height limits, minimum parking requirements, apartment etc. Their results suggest that a less restrictive approach to urban planning that enabled sufficient supply to housing would reduce the rate of house price inflation by 50 percent with net benefits of $1.4 billion to $10.7 billion over the 2001-2013 period.

The viewshaft policy costs Auckland economy $1,366 billion

Cooper & Namit (2021) investigated the impact on house prices of Auckland’s viewshaft policies which restrict development to protect regionally significant views, to volcanos and the museum, for example. The CBD Viewshaft, for example, covers 1.7 million square metres of land. They used 2014 property (rating) data29 and viewshaft information from Auckland Council. The study uses a robust regression discontinuity method and accounts for the difficult to quantify benefits of viewshafts. Their results suggest that land values per square metre within 75 metres of the viewshaft are $1,282 higher than those located farther away (between 75 and 175 metres from the viewshaft boundary). Figure 19 shows the land values at different distances from viewshaft. Accordingly, for the properties located at the distance of 100 metre from the viewshaft, the estimated difference between land values per sqm for properties inside the viewshaft are on average $2,535 lower than the properties at the same distance located outside the viewshaft. After controlling for other features of land, the difference increases to $2,939. They conclude that the net cost from the viewshaft policy to the Auckland economy is $1,366 million (per year).

Figure 19 Land values and distance from viewshaft

Source: Cooper & Namit (2021).

Grimes & Aitken (2006) studied determinants of new housing supply and the impact of supply responsiveness on price dynamics. Their results show that a 1 percent increase in house prices relative to total development costs raises new house supply with an elasticity of between 0.5 and 1.1 percent. Since the study has controlled for land prices, the estimated low response of the housing supply (to price increases) is likely driven by regulatory restrictions in the housing market. The authors also note that land prices have a strong impact on new house construction. A 1 percent increase in land prices is estimated to lift total development costs by 0.33 percent, which in turn leads to a 0.37 percent decrease in supply of houses. The data used is a quarterly dataset of median house prices for New Zealand over the period of 1991Q1 to 2004Q2 covering 73 Territorial Local Authorities from QVNZ. Given the lack of granularity of their data, the study does not provide more information about potential variations across location.

Greenaway-McGrevy (2018) assessed the impact of land use regulation on house prices in the Auckland region. They used a difference-in-difference (DiD) method and a unit level dataset of house sales for their assessment. The authors compared house price sales for property pre and post the Auckland Unitary Plan to test price effects of up-zoning (i.e., relaxing a restriction on site development). Their results suggest that up-zoning generated a significant increase in prices for underdeveloped properties relative to highly developed properties and properties that were not up-zoned; up-zoning in the most intensive residential zone generated a premium of 22.2 percent.

Parker (2015) uses the results of Bertaud, (2014) to show that Auckland’s population density is significantly higher in the CBD and almost flat in other areas. He discusses that the impacts of planning constraints are reflected by the non-continuous rate of population density in Auckland compared to other metropolitan areas (for illustration of the non-continuous density in Auckland see Figure 22). He argues that planning constraints that cause the need to build on progressively, more difficult sites lead to lower construction productivity. Additionally, planning constraints cause difficulties in buying large land areas for efficient scale development. Changes in population/dwelling density over time could provide more information about potential impact of policies. We will discuss this further in the next section, to provide an understanding of the potential impact of the RMA.

Grimes & Mitchell (2015) conducted interviews with 16 developers, providing information on 21 developments across Auckland to assess the costs of the rules and regulations (as perceived by developers).30 Their results suggest that building height limits and balcony requirements can each have costs impacts of over $30,000 per apartment. The council’s desired mix of typologies and increased minimum floor to ceiling heights can each add over $10,000 per apartment. For the residential section and standalone dwellings, infrastructure contributes not related to a specific development cost at around $15,000. These includes costs such as extended consent process, section size requirements, and other urban design considerations. They also assessed the potential loss in development capacity31 from council’s rules and regulations. Their results suggest a median loss in capacity of 22 percent (for the developments that proceeded).

Norman et al. (2021) used GIS mapping to illustrate that a higher land value correlates with high density housing areas. Assuming demand is highest at the city centre, they show that the Auckland Council’s zoning is not consistent with where demand is the highest.

Cavalleri, et al. (2019) use a stock-flow type model of supply and demand using panel data from 25-countries, between 1980Q1 and 2017Q4. They used an index as a proxy for land-use restrictiveness.32 Their findings suggest that: regulations that restrict housing tend to result in more vacant houses; regulations exacerbate mismatches between supply and demand; rent controls reduce the responsiveness of housing supply to demand pressures (though the effect is small); and that limits to urban expansion (geographic and regulatory) reduce incentives for new construction. > Mayer & Somerville, (2000) used quarterly data from a panel of 44 U.S. metropolitan areas between 1985 and 1996 to study the impact of house prices and costs on new housing construction. Their results suggest that metropolitan areas with more extensive regulations can have up to 45 percent fewer housing starts and price elasticities 20 percent lower than those in less-regulated markets. Also, their results suggest that a 1 percent increase in house prices temporarily increases new construction by 15 percent over current and following 5-quarters. The results of their modelling suggest that the regulations that lengthen the development process have an uneven temporal effect on supply elasticity.

Urban growth boundaries have led to HPG High agreement, High evidence

Based on the previous literature, the Productivity Commission's (2012) housing affordability inquiry, the price of land is responsible for between 40 and 60 percent of the cost of new dwellings in Auckland (in 2012) and is a driver of house price inflation. The inquiry refers to the results of a model that they estimated and identified the Auckland MUL as a driver of supply side rigidity. Our review of their model suggests that that there is a range of related factors that have not been accounted for in the model and may affect the results of their estimations. However, their results are consistent with the outputs of other studies using more comprehensive economic modelling frameworks.

Parker (2021) provides a comprehensive (theoretical) economic framework for the assessment of the impact of a competitive land market on house prices. His framework is based on a well-known economic modelling framework – AMM (Alonso-Muth-Mills model), which was widely used in previous studies in New Zealand.33 Parker discusses that, in an uncompetitive market, land prices on the fringe of the city depend on the bargaining power of households (demand for residential land) and farmers (demand for agricultural land). The output of his economic framework suggests that, in an uncompetitive land market, where there is a cap on the urban growth boundary, the price of residential land increases as a result of regulation, as illustrated in Figure 20.

Figure 20 Urban boundary limit leads to an increase in residential land prices

Source: Parker (2021). The horizontal axis shows distance from the city centre and the vertical axis is the price of land.

The prominent study of Grimes & Liang (2009) on the impact of the MUL on land prices has been cited widely as an indicator cost of regulation. We consider MUL regulation as an environmental regulation as its successor, the Rural Urban Boundary (RUB) under the Auckland Unitary Plan is denoted as a district plan land use rule pursuant to section 9(3) of the RMA. The authors study the difference in land prices between parcels located inside and outside of the urban boundary. Their results suggest that land inside the boundary is significantly more expensive than the land outside the boundary by a factor of between 7.9 and 13.2. As the authors noted, they do not have any information about the value of infrastructure that has been potentially capitalised into the land values inside the MUL.34 Also, the timeframe of the available data does not provide them any information about land prices before and after any MUL expansion. This study provides valuable information about the price increases associated with limitations imposed by MUL regulation.

Martin & Norman (2020) study the price difference between the land inside the RUB and the farm land outside the boundary.35 Consistent with the results of the previous studies, their study suggest the existence of a price premium for the land inside the urban boundary. However, their results suggest that converting farmland or lifestyle blocks into bulk-infrastructured residential sections would be unlikely to deliver land to the market substantially cheaper. Our review of the methodology of their study suggests that some of their assumptions have a significant impact on the results. For example, they refer to plans that suggest between 55 and 58 percent of land outside the urban boundary is unavailable for development, but they assume that only 35 percent of land outside the urban boundary is unavailable. This assumption is not justified and likely affects their results significantly. Our review of their methodology suggests that they have not used the location of the urban fringe in their analysis.

Zheng (2013) studied the impact of the MUL on land price. Consistent with earlier studies (for example, Grimes & Liang (2009)), his results suggest that the Auckland metropolitan urban limit results in upward pressure on residential land prices within the urban areas. His results show that the impact is uneven with a larger impact on land at the lower end of the price distribution. Also, when the supply of land on the urban periphery is restricted, the price of available residential land rises and new builds tend to be larger and more expensive houses.36

For the review of the impacts of the RMA and other regulations, it is important to differentiate between the impact of the regulation and the costs imposed from implementation of the regulations. The RMA categorises the activities that may exceed the limitations introduced by discrete plans to six categories, namely permitted, controlled, restricted discretionary, discretionary, non-complying and prohibited. The ‘activity category’ is a policy setting that determines the degree to which each element of a plan binds. The permission required for undertaking the activities that may affect the environment is called a ‘resource consent’ or ‘planning permission’. There is a chance of a regulatory impact on the probability of granting a resource consent. Torshizian (2015) defined ‘permissibility’ as the effective permission level granted by an activity status category. He investigated the permissibility of Auckland Council’s activity statuses and its impact on regional development. His results indicate that, once the characteristics of the activities are taken into account, a difference remains between the likelihood of different activity categories, and that interpreted as the bias associated with RMA regulation. Accordingly, the activity category ‘restricted discretionary’ (which restricts the scope of consideration to planners) is approximately 20 percent less permissive than ‘discretionary’, which is meant to be a more involved affair. His results suggest that the change in permissibility of the restricted discretionary activity has happened after the amalgamation in 2010.37 Also, after the amalgamation in 2010, the average likelihood of all activity statuses decreased by a factor of between -1.3 and -2.7 percent.38

Bassett et al. (2013) reviewed New Zealand’s housing affordability problem and the development of housing in New Zealand since the early 1900s. They provide a comprehensive review of the role of central and local governments in planning regulations over time. They argue that the lengthy and costly process of releasing land outside the Metropolitan Urban Limit (MUL) in Hobsonville, Flat Bush, Papakura, Karaka and Silverdale, between 1989 and 2010 was very costly (both in terms of expensive hearings and the social and economic costs of slow regional development).

Fernandez et al. (2020) studied the impact of proximity to Wetlands on residential property prices in Auckland. Their results suggest that proximity to natural wetlands is associated with lower house prices, but the interaction of artificial wetlands with parks is associated with higher house prices. They mention the importance of school zones on house prices, but do not account for that in their estimations. Their study does not account for proximity to other amenities and facilities and does not investigate causal relationships.

Cooper & Namit (2021) investigated the impact of Auckland’s viewshaft policies on house prices. Accordingly, the CBD Viewshaft covers 1.7 million square meters of land. Their results suggest that land values per square meter within 75 meters of the viewshaft are $1,282 higher than those located farther away (between 75 and 175 meters from the viewshaft boundary). They conclude that the net cost from the viewshaft policy to the Auckland economy is $1.4 billion (per year). The study uses a robust regression discontinuity method and accounts for the difficult to quantify benefits of viewshafts.

In an international study, Kallergis et al. (2018) investigates housing affordability across 200 cities.39 Their results suggest that a 10 percent increase in urban extent density leads to an 0.8 percent increase in price-to-income ratio. In the cities with enforced containment40 the price-to-income ratio is 1.6 percent higher than average. The advantage of this study is the large sample of the cities that they have included in their analysis. However, the analysis controls for a very few related variables to urban limit regulation and the results may not be interpreted as causal effects.

Table 3 Difference in land values across the RUB

| Author | Multiplier | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Grimes & Liang (2009) | 7.9 – 13.2 | Controlling for area unit effects found a boundary effect of 5 – 6 in 2001. However, is likely to reduce the estimated boundary impact and underestimate results. |

| MBIE & MfE (2017) | 3.15 | Auckland is 3.15. Ratios of 1.53 - 3.15 depending on geographic area. |

| Zheng (2013) | 1.3 - 9.7 | Lowest price decile 9.7, Median price 5 Highest price decile 1.3 |

| Productivity Commission (2012) | 7.15 - 8.65 | 7.15 in 1995, 8.65 in 2010 |

| Martin & Norman (2020) | 0.006 – 0.052 | For residential-sized lands inside the Auckland RUB 2020. |

Source: Grimes & Liang (2009); MBIE & MfE (2017); Zheng (2013); Productivity Commission (2012); Martin & Norman (2020).

The studies reviewed above have discussed the impact of regulation on house prices. The literature on the impact of regulation on house price growth is limited. Torshizian (2018) estimated the impact of MUL expansion on house price growth in the Auckland region. This is the only study that captures the impact on prices of houses located in different proximities to the expanded area, before and after the expansion. The study captures the impact for the suburbs located nearby the expanded area and compares that with the suburbs with similar opportunity to expand. For benchmarking, the study uses the price growth of houses compared to the houses with similar price range located in the central area (which are not directly affected by an urban expansion). Results suggest that:

the price growth in expanded areas is similar to the central areas,

the price growth in areas nearby the expanded area is similar to the other areas with similar features, and

the price growth outside the urban boundary is significantly higher for areas located closer to the expanded area.

The author concludes that the reason for high price growth in the areas located outside the boundary and nearby the expanded area, is their expectation of future growth in their area.41

This expands the findings of the other studies by providing evidence for the lack of competition in the land market being a driver of house price growth. Accordingly, the lack of competition resulting from the MUL is associated with an average of 13 percent higher house price growth. This is equal to an average of 0.31 percent additional cost to the land values, which is equal to $4,730 (in 2021-dollar values).

Geographic constraints have not been the driver of HPG High agreement, Medium evidence, Medium certainty

As described, many studies of the regulation impacts do not directly account for the impact of geographic constraints. This is due to measurement issues. Given the robust economic assessment framework that these studies used and the high agreement across the studies, we conclude that the impact of geographic constraints on the findings of the studies of costs of regulation is insignificant.

Saiz (2010) investigated the impact of geographic constraints on urban development using GIS derived data (coastal areas and land steepness) for metropolitan centres in the U.S. over the period of 1970 – 2000. The findings show geographically constrained areas tended to be more expensive, with faster price growth. Furthermore, antigrowth local land policies are more likely occur in growing land-constrained areas.

Nunns (2019) provides an estimate of the likely costs imposed by geographic constraints. He defined geographic constraints as a lack of flat developable land.42 His results suggest that a 1 percent increase in geographic restrictions is associated with $39 per sqm higher land prices.

2.2 Impact of the RMA and environmental regulations

Description

The RMA and environmental regulations impact housing through their guidelines for councils’ planning regulation developed based on the RMA. Currently, the RMA is going through a reform. A successful reform will support the NPS-UD agenda, by improving the competitiveness of urban land markets43, and go beyond the requirements of the NPS-UD by providing a more certain regulatory framework that will lead to higher certainty around planning regulations.44

Summary of literature review

The literature on the impact of environmental regulation on HPG is limited. This is partly because of the overlapping impact of the RMA and the planning regulations. For example, it is not clear how much of the costs imposed from an urban-rural boundary regulation are because of the environmental limits imposed by the RMA versus the planning targets of intensification. The limited literature on the impact of environmental regulation is not supported with strong evidence. However, there is high agreement in the literature that a more transparent, permissive and well-monitored resource management regulatory regime leads to lower social costs through its impact on the planning regulations.

Most of the literature we include in this section is based on conference and policy papers and a parallel study of the impact of Resource Management reforms. For a robust understanding of the impact of RMA, we need further robust assessments using granular geographic data. The interaction between the environmental regulation and other legislations (and infrastructure planning) needs further investigation.

Uncertainty assessment: RMA has led to HPG (or the driver of costly planning regulation is RMA

There is not a clear distinction between the impact of environmental and non-environmental regulations. The impact of environmental regulation is mainly on the land use, which is expressed as the reason for the zoning regulations. The primary impact of land use regulation is on urban growth boundaries (at the periphery of the city) and the resource consents’ level of permission for different activities. The linkage between the zoning regulations and the RMA, however, is not supported with evidence. We reviewed the literature on the impact of urban growth boundaries in the previous section. While the urban growth boundary is not a restriction (directly) imposed by the RMA, a successful resource management legislation must provide clear instructions about its implications for the planning regulation (and monitor correct implementation).

Parallel to this review, Resource Economics, Principal Economics and Sapere (2021) assess the impact of RM reform. They discuss that the outcomes of councils’ planning regulation (driven by the NPS-UD), if accompanied by a permissive and transparent RM system, can lead to higher benefits than those from the NPS-UD alone. As shown in Figure 21, the combination of the features of the RM system and their interactions with the councils’ regulation may lead to a wide range of outcomes for the housing market.

Figure 21 Combined impact of RM system and planning regime

Source: Principal Economics.

The pattern of dwelling density in Auckland before and after the RMA effects come to existence in 1991 are shown on the left-hand side of Figure 22. As illustrated, the pattern has changed dramatically over time.45 This is consistent with the changes in pattern of land values illustrated on the right-hand side of Figure 22. The comparisons between the two graphs shows the high correlation between patterns of dwelling density and land prices over time.46

As shown in Figure 12, there has been many legislative changes over the 1980-2020 period that may have been associated with this change in the distribution of houses and prices. For example, the RMA and the local government reforms in 1989 led to widespread changes across New Zealand local governments. The 1989 reforms led to a decrease in the number of local governments by 90 percent (from 828 to 86 in 1989). The RMA played a complementary role to the 1989 local government reforms. There is a more careful assessment of the impact of the two reforms on providing enabling and effective development outcomes required.

Table 4 High level housing outcomes of NPS-UD and RMA and the RM reform

| Outcomes | NPS-UD & RMA | RM reform |

|---|---|---|

| Affordability | NPS-UD has a range of recommendations contributing to housing supply elasticity, including:

competitive land markets and high-quality greenfield development |

- National direction and more clear legislation leads to decreases in consenting cost which translates into allocative efficiencies - Housing supply is responsive to demand, with competitive land markets enabling more efficient land use and responsive development, which helps improve housing supply |

| Choice | Improving housing choice through: - increasing planning flexibility. - aiming for agglomeration benefits – i.e. larger or denser places tend to provide greater variety of services and consumer goods |

Increase housing supply to better meet residents’ demand for housing (by type, size, location and price) |

| Māori participation | Recognise Te Tiriti and contains provisions aiming to enable Māori participation in the system | - Enabling the housing aspirations of Māori such as by enabling papakāinga developments - Providing opportunity for Māori to participate as Treaty partners across the RM system, including in national and regional strategic decisions. Māori will be sufficiently resourced for duties or functions that are in the public interest |

| Climate change | Better prepare for adapting to climate change and risks from natural hazards, and better mitigate emissions contributing to climate change | A reduction in transport carbon emissions versus the status quo from more efficient land use patterns through improved spatial planning |

| Improved System performance | Focused on improving effectiveness of planning regulations | Improve system efficiency and effectiveness, and reduce complexity, while retaining appropriate local democratic input |

The RMA reduces the responsiveness of housing supply high agreement, medium evidence, medium certainty

A successful RM system provides:

a regulatory framework that leads to higher certainty around zoning regulations.

a more flexible housing supply through providing a more permissive regulation and allowing more flexibility in housing supply.

Given the complementary roles of the RM system and the NPS-UD, Resource Economics et al (2021) discuss that the total impact of the RM system and NPS-UD is to achieve a responsive housing supply. To distinguish between the impact of the RM system (and the reforms) and that of the NPS-UD, we can use estimates of the impacts of an improvement in the resource consent process and its impact on land values. Any impact on land values in addition to the estimated impacts of resource consent is likely driven by the NPS-UD.

The RM system (and the reform) provide a national level direction (or centralisation). This leads to a decrease in the chance of negative externalities from one region’s urban growth on other regions;47 and an increase in certainties around permitted and prohibited activities (with less room for discretion). Also, one of the objectives the reforms is to decrease the number of Acts to resolve any potential inconsistencies across different pieces of legislation leading to a higher certainty/transparency level.